Career Snapshots with Joshua Hyke

Michael Schubert interviews Joshua Hyke on his career as a med tech in Infection Prevention

| Video

Joshua Hyke

Infection Prevention Specialist

Froedtert and The Medical College of Wisconsin, USA

What led you to the lab – and from there to Infection Prevention?

I started out wanting to be a pathologist, but things weren’t working out on the road to med school, so I tried to find a different program in which I could be as close to pathology as possible. I found clinical laboratory science and my advisor said, “This would be a great route for you.” I ended up graduating with a degree in clinical laboratory science and became an ASCP-certified medical technologist.

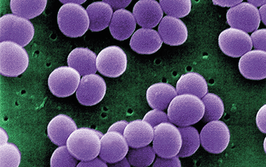

I started in a microbiology lab here at Froedtert Hospital, where we had a forward-thinking, innovative medical director who was interested in increasing the lab’s technology. In 2006, when I started, we had just begun molecular testing for all the microorganisms we test for in the lab – but we were still mostly doing viral cultures and those sorts of things. Then, my medical director decided to start adding on technology such as PCR, making it affordable to patients in the best way they could while also yielding much quicker, more sensitive, and more specific results (depending on the bugs we’re looking for).

I worked in the microbiology lab for about 10 years, eventually gaining a full immersion into molecular diagnostics and becoming a supervisor of the second- and third-shift staff. With that, I also learned how to do research along with my medical director, who was big on doing validation studies on novel technology that we were bringing in. I got the full breadth of experience while I was in the lab and, after about 10 years, ended up trying to figure out – what can I do next?

One thing about working in the lab is that you’re away from patients. Some people really like that, but others – including me – want to be a little bit closer. My medical director was approached by a colleague in the infectious disease department asking if there were any med techs who might be interested in infection prevention and control. He told me about it and I said, “Yeah, let’s look into it!” I interviewed for it and the director of infection control at the time was very interested in me. I was hired and I’ve been in the position for about six years.

Describe a “day in the life” in Infection Prevention…

I come in to work and I immediately do infection and isolation surveillance. Froedtert Hospital has 600-plus beds. There are six infection preventionists (Ips) on the team, each allotted certain parts of the hospital. I oversee the medicine department (five or six patient care units) for surveillance. Anytime there’s a positive lab that requires a patient to be in isolation, such as an antibiotic-resistant organism, I have to make sure that patient gets into isolation. I also do hospital-acquired infection surveillance. The “big ones” are central lines for bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections. We also have a lot of ventilators; even before COVID-19, we had a lot of patients in ICU who required ventilation and we do surveillance for ventilation-associated pneumonia as well. We also do surveillance for Clostridium difficile infections because those are big in terms of antimicrobial stewardship and test utilization management. I learned a lot about those things working in the lab, but as an IP, I’m very passionate about understanding the doctor’s perspective. From an IP standpoint, we’re very much surveillance-based, but the clinical aspect is not as black-and-white. So we work with the staff who care for the patient – from the doctor all the way to even the person who cleans the room – to figure out what the best move is for a particular patient, especially if they have an infection that requires IP investigation or isolation.

I also have a lot of meetings – planning meetings and review meetings to make sure our processes are up to date. If we have, in the last three months, had a unit with – for example – a higher incidence of C. diff infections than before, we do an action plan with the unit’s nursing and physician leadership to figure out what steps we can take bring the number to come back down to industry standard or below. In that case, I also answer a lot of questions in microbiology thanks to my lab background; I’ve noticed that the work of the lab is not necessarily well-known among floor staff.

When it comes to taking care of patients, especially directly (such as when collecting a swab for a wound), there are certain techniques you have to use that not everyone knows. It’s not always a huge part of nurses’ education – and physicians may not get much exposure to microbiology in medical school. I’ve even helped educate my fellow IPS on some of the lab work we used to do and helped them understand what the different results and reports mean.

I also oversee construction projects. When I was interviewing, my director asked if I had any experience with construction. The only thing I could say was that I’d remodeled the bathroom once – but she said, “That’s more than I have!” So I got immersed in the world of hospital construction. A big piece of that is determining the construction site’s risk to the patient population. Having a clinical background makes me an important member of the construction team in terms of monitoring air quality, verifying containment, and ensuring that the water we’re putting into a new space is safe and that there’s no risk of Legionella, coliform bacteria, fungus, or mold. We have to make sure that our construction sites are safe and that our staff and patients are kept safe during and after construction. That takes up more than half of my day, which is fascinating, because it’s not a job that most people think about in relation to the lab.

What lab skills have you found most valuable in Infection Prevention?

For me, it’s knowing what the pathogens and normal flora are. And, because you learn a lot of pathology as a med tech, you understand how the pieces of the puzzle interlock in a patient’s clinical picture – why they’re in the hospital, what their comorbidities might be – and you can combine that with the knowledge you gain from the microbial identification you do. Having that knowledge has helped me immensely; it has given me the ability to read a patient’s chart and lab results and have a good idea of what I’m looking at.

For example, if I see a certain bug in a patient’s test results, I can better focus the action plan we develop. “Okay, this looks like it could be a skin bug. How could it have gotten there on this patient? Is this patient scratching their insertion site? Are they inadvertently contaminating the line themselves?” I’ve had patients who are not very compliant in their daily hygiene care and others who pull their lines or catheters because they’re uncomfortable.

But you don’t have to be a microbiologist to be a good IP. It’s enough to have a background in clinical lab science and the ability to problem-solve and recognize when something doesn’t make sense. One of my bosses in the lab told me, “I can train you on how to read a result on a computer in about two seconds. But you have to learn to think about how that result might not make sense and troubleshoot it.” That’s part of what we do in infection control. Every once in a while, you have to step back and say, “Okay, it’s not all adding up. What else could it be?” That’s something clinical laboratory science folks understand well – and it’s very important in IP.

What’s your favorite part of your work?

My favorite part of my work is the construction stuff.

When I first started as an IP, we were doing a huge project – building multiple floors on top of an existing building. I was out there in a hard hat, standing on the roof overlooking the city of Milwaukee in the distance, and thinking, “This is something I would never have thought of as a lab tech.” That was pretty cool.

The other thing I really like is overseeing compounding pharmacies. They remind me a lot of parts of the microbiology lab where you work in negative pressure rooms and places that are sterile to avoid contamination. When you’re doing sterile compounding of IV drugs, you use a lot of the same techniques in the hood to ensure that ensure that the drugs are sterile before being administered to patients. The pharmacists are interesting people to work with, too. I grew up with a parent who is a pharmacy tech, so working with them has been really interesting for me.

Finally, one of my units specializes in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. I’ve learned a lot about CF, particularly with respect to antimicrobial stewardship and understanding more about how we care for CF patients. They’re not just bacteria on a plate; we interact with the patients and take different isolation precautions to make sure that they are not exposed to a bug their system wouldn’t be able to handle the same way yours or mine would. That has been a very interesting journey for me as well and something I’ve thoroughly enjoyed.

What one key thing would you like to share about what you do?

I would just like aspiring and early-career laboratory professionals to know that they have the skills to do this job well.

We have three former lab techs and three nurses on our team; all of us have different backgrounds. One of my colleagues used to work in the microbiology lab with me, but focused on different things. Another has a PhD in immunology. We have an ICU nurse, an ER nurse, and a medicine floor nurse, too. I’ve been able to teach the lab piece to other people, which helps the lab world “come out of the basement” and gets other staff in the hospital to really understand and respect the work we do.

Our lab background also makes it easier to learn some of the nursing pieces. I didn’t know anything about central lines before I became an IP, but my nursing colleagues taught me how those types of devices work. Having the background on what’s going on inside the body from the lab also helps me understand those devices and all the other things we use to care for patients on the floors. Traditionally, IP is thought of as mostly a nursing profession, and your managers, directors and VPs are usually nurses – but there’s starting to be a lot more appreciation for med techs in the field. When I was trying to get an IP job, it was always, you know “Bachelor of Nursing at minimum,” but we’re slowly working past that and building diverse teams of professionals. For any lab tech who wants to get involved in more direct patient care, IP is a great avenue to pursue.