Beyond Stone-Age Sample Prep

Miniature detection technologies are evolving fast – but unevolved sample preparation is holding us back.

Miniature detection technologies have matured over the last decade thanks to significant investment from industry, funding agencies and investors. We can accurately identify target compounds using myriad technologies, including biosensors, spectrometers, PCR and sequencing. Highly abundant molecules, such as sodium and glucose, can now be monitored from a single blood drop using handheld systems, such as the i-STAT.

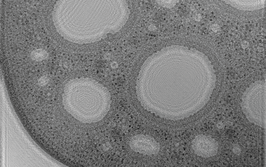

Unfortunately, when the target is of low abundance or contaminated with other substances, we’re still struggling. Prevention of sepsis, food poisoning and water contamination, as well as the diagnosis and monitoring of cancer, all depend on the timely detection of rare targets – pathogens and circulating tumor cells. In these cases, we still rely on a series of cumbersome processes to convert the sample we gather into suitable fractions for analysis. Sample preparation currently relies on a suite of instruments for centrifugation, re-suspension, lysing, filtering and sorting; cue extensive labeling, wet chemistry and endless pipetting – all carried out manually so that reproducibility is too often dependent on experience...

Detection of one pathogen or tumor cell in a 10 mL sample is commonly required in clinical diagnostics (and in environmental monitoring, there can be as little as one target per liter). To obtain statistically valid results in these applications, we have to process large samples. It is unrealistic to expect the accurate and precise detection of a low abundant target when sampling only a few microliters of sample from a patient or water supply. Hence, preparation of large sample volumes is quite often a necessary step to enrich a target and enable analytical techniques. For example, lateral flow assays can only detect targets at a concentration of 100 nM. Even analytical technology with sensitivity of 1 attomolar would require at least one target per microliter of sample.

Is there a solution to this “needle-in-the-haystack” problem? Well, transforming samples retrieved from a real-world scenario into ideal fractions for analysis is by no means a trivial task. But the reward is worth the effort, and a number of promising technologies for sample handling, particle and molecular sorting, and lysis are being developed. These include contained platforms such as centrifugal microfluidics and digital microfluidics; and label-free bioparticle sorting, such as dielectrophoresis, inertial microfluidics, deterministic lateral displacement, and acoustophoresis.

There is much work to do before these next generation techniques can prepare a sample at the touch of a button. I foresee a combination of these techniques gradually enriching a target in a decreasing sample volume over time. Multi-scale fractionation of sample components will allow us to tailor the fraction depending on the analysis to be performed. Importantly, we will also need standards that enable the integration of modules developed by different companies; for example, standardizing the connector for transfer of a given sample type.

Improving throughput, efficiency and reproducibility of a technology, and its integration with others, are not incremental advances. They are enablers of a practical platform that can have tremendous impact on clinical diagnostics, as well as disease diagnostics in rural, space, battlefield and wilderness scenarios. Investors and funding agencies first need to understand the challenge of sample preparation – and then do more to reward our efforts.

Rodrigo Martinez-Duarte is an Assistant Professor at the Multiscale Manufacturing Laboratory, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Clemson University.