The Great Laboratory Greenwash

Wading through the marketing sludge to sort the sustainable from the psychological

By George Francis Lee

Listen to this article in the author’s voice

Credit: Wikimedia

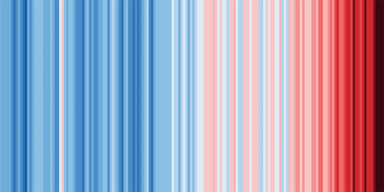

Blue and red are the colors of our times. No, not because of a worldwide bout of US patriotism, but because of the power of data visualization. What I’m referring to is warming stripes, also known as climate stripes – an image that has quickly become an emblem of man-made climate change. It is a terrific – and terrifying – way of visualizing global temperatures in simple red, white, and blue. No wonder the stripes have entered the public consciousness – everywhere from Greta Thunberg’s debut book cover to the very cover of this magazine. Whether we like it or not, warming stripes are the aesthetic of the anthropocene.

But another color – a less urgent, friendlier, secondary shade – is also prominent in our minds. It is the color perhaps most associated with the term eco friendly – and it appears to have become a license to hoodwink the less savvy. While we’ve all been “thinking green,” some marketing minds have been busy greenwashing.

Painting the lab green

Greenwashing is a tried and tested marketing technique. The term was first coined and codified in 1986 by environmentalist Jay Westerveld, but one of the earliest cases of the “green sheen” actually goes back to the 1950s, when Keep America Beautiful’s campaigns got the ball rolling on environmental action shaped by individuals and responsible consumerism (1). It’s a devilishly simple process to understand; to quote the Oxford English Dictionary, “greenwash” means:

“To mislead (the public) or counter (public or media concerns) by falsely representing a person, company, product, etc., as being environmentally responsible…” (2)

Following its rise in subsequent decades, there has been plenty of pushback from activists and experts who want to help consumers realize the actual impact of the companies they purchase from. Today, the average consumer can simply search for a multinational corporation and find out about all of their dirty deeds in horrifying detail (3).

But for laboratory professionals, wading through the greenwash is less simple, “...a manufacturer may claim their product is recyclable, but municipal recycling centers can rarely accept medical or laboratory devices in their handling processes,” says Karin L. Zuegge, Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Medical Director of Sustainability at the University of Wisconsin, US. “Imagine a waste handler being faced with emesis basins, syringes, pipettes, or petri dishes; then trying to figure out if these are contaminated and where to put them.”

Though not a laboratory scientist, Zuegge has years of experience making her university reduce its output of emissions and waste. She also co-authored Greenwashing in Health Care Marketing (4) back in 2020.

Like many in healthcare, Zuegge got her start in sustainability by simply noticing that her place of work produced a lot of waste. After all, it’s estimated hospitals and labs are responsible for 4.4 percent of global emissions (5). “I observed how much we seem to throw away in the hospital and started on my healthcare sustainability journey by simply asking how much garbage we produce,” she says. “Trying to quantify the waste opened my eyes to the enormous scale of this issue.”

Credit: Polina Tankilevitch / Pexels.com

But as Zuegge correctly identifies, there’s a disconnect between the intentions of well-meaning healthcare providers and clever (or deceptive) marketing spin. “There is some skepticism about marketing techniques, but these techniques are nonetheless designed to make us want to purchase items that companies want to sell.”

“There is a flood of information available to consumers – privately and professionally – and this can be overwhelming. We are experts in our fields, but not everyone is an expert in spotting false claims or making smart purchasing decisions. The very nature of marketing is to make something look good and sell it, and we are naturally attracted to these techniques.”

Psycho-sustainable

We like to purchase products that are associated with values that we deem important – regardless of whether they actually reflect those values or not. One study saw that people were more likely to choose a product based on “green appeal” if they were in the presence of others, responding to a kind of “anticipatory guilt” (6). Effectively, this means that companies can apply psychological pressure to encourage sales. When faced with an unknowingly greenwashed product, there is a high probability that an eco-conscious consumer will purchase it (7).

Credit: CHUTTERSNAP / Unsplash.com

It does not seem a stretch then to say that, if companies can greenwash without arousing suspicion, there is a lucrative cohort of consumers ready to offer their cash.

As Zuegge puts it: “As we all become more aware of the benefits of sustainable choices, and the pressure to avoid negative environmental impacts in our day-to-day choices increases, showcasing the greenness of certain products is an effective strategy. Marketing a product as environmentally harmless or beneficial makes it more appealing. We want to believe what we are doing is good for people, health and the environment – so these strategies are attractive.”

Giving the green light

So, how do we separate the genuine from the greenwashed? That’s the question I posed to Andy Evans, Director of Green Light Laboratories – an independent lab sustainability consultancy.

Since 2009, Evans has been working in sustainability with some of the most well-known universities and organizations in the UK, and has a treasure trove of case studies on how lab equipment performs. More recently, Green Light Laboratories has even been contracted to write the testing procedure for all laboratory cold storage units for the UK.

“Not all greenwashing is ‘in-your-face’ obvious,” says Evans. “The devil is in the details and we endeavor to show people how to spot – and avoid – greenwashing. We train researchers, building managers, and procurement professionals how to dissect marketing materials and spot greenwashing. It’s so empowering for them.”

Greenwashing red flags, provided by Andy Evans

- Pictures: Trees, leaves, and green color schemes

- Data: If it’s not quantified, it’s no use to you. Seriously, ignore pretty colors and 1–10 ratings.

- Data: If it is quantified, where has it come from and what is it compared to?

- Language: The use of authoritative language, framing the material as factual. Always remember you’re reading marketing materials.

Evans emphasizes data above all else, and recommends that everyone – customers and companies – should be using quantified data under clear and universally agreed upon methodology. To him, we all should “only use quantified data that is generated under lab conditions…” and “avoid products that have a label which quantifies no carbon or relies upon standards that are inadequate in reflecting modern requirements.”

Without data, it seems we are doing little more than satisfying our own sense of guilt. “Sometimes these alternatives are great,” Evans says, as I anticipate a big “but”...

“But we are finding that some of the ‘innovative’ products may be just as bad for the environment. They can even have hidden costs that make them far more expensive to operate than advertised. Again, this comes down to where manufacturers get their data – and what they don’t include.”

Sustainability tips, provided by Andy Evans

- Sign up to LEAF. This is the leading Lab Certification Scheme globally.

- Join the Laboratory Efficiency Action Network (LEAN) network. This group freely shares their experience and expertise in all things lab sustainability. Think of any big research organization or university and they’re probably on LEAN. [Editor’s note:] There is also the Sustainable European Laboratories network and International Institute for Sustainable Laboratories.

- Shameless plug: Get me in to do a day’s training! You’ll be well equipped to tackle your current and future challenges.

Credit: Markus Kniebes / Flickr.com

Clearly, the vacancy of a universal standard allows for-profit companies to measure their eco credentials with yard sticks that only they can see. Evans believes that manufacturers and distributors can be trusted not to greenwash, but only if they all use the same standards to generate their quantified data. “At the moment some suppliers have their own criteria to define aspects of performance. This is, whether intentional or not, misleading,” he says.

Zuegge, on the other hand, thinks that regulation could be useful. “Green labels for devices or requirements to disclose working conditions in factories where items are produced could push companies in a socially and environmentally responsible direction,” she says.

“Consumers will eventually demand transparency and possibly also demand regulation,” she adds. “Responsible regulation could certainly help pressure companies to be more sustainable on a shorter timeline – before it’s too late to prevent the worst effects of the climate crisis.”

Unfortunately for us, Zuegge’s last point brings us back to what kick-started this piece. If we continue to ignore the emissions that are tied into our professional lives, we will continue our trajectory toward climate catastrophe in a not-so-unconscious form of self-sabotage. And even as some people attempt to drag humanity out of this self-dug hole, others come up with inventive ways to kick us back in. But, hey, look on the brightside: At least they’re wearing green boots.

- DP Barash, “‘Keep American Beautiful’ and Personal Vs Corporate Environmental Responsibility,” (R)evolutionary Biology, History News Network (2020).

- OED Online, "greenwash, v." (2023). Available at: https://bit.ly/43ECqNC.

- ClientEarth, “The Greenwashing Files” (2023). Available at: https://bit.ly/43f5Bqj.

- D Gordon, KL Zuegge, “Greenwashing in Health Care Marketing,” ASA Monitor, 84, 18 (2020).

- NoHarm, “Health Care’s Climate Footprint” (2019). Available at: https://bit.ly/3WsD7r2.

- J Peloza et al., "Green and Guilt Free: the Role of Guilt in Determining the Effectiveness of Environmental Appeals in Advertising," Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, Adv Consum Res, 38 (2011).

- J Volschenk, et al., “The (in)ability of consumers to perceive greenwashing and its influence on purchase intent and willingness to pay,” South African J Econ Manag Sci, 25 (2022).