AI: Hinderance or Hero?

As technology advances, does artificial intelligence present benefits or complications in the clinical lab?

Jessica Allerton | | 3 min read | Discussion

Is pathology in a generative AI era? As technology continues to advance and the use of large language models like ChatGPT becomes the norm, researchers are exploring both the potential and limitations of AI in digital pathology.

Here at The Pathologist, we’ve shared many views of professionals in the field – most of them in favor of adopting AI in the pathology lab, such as Judith Sandbank’s exploration of AI-augmented pathology for advances in cancer diagnosis and research.

But what happens when even the most basic digitalization goes awry?

In July 2024, pathology services at the University of Southampton, UK, transferred to a new electronic laboratory information management system (LIMS). The transition proved more complicated than anticipated and blood testing suffered a huge delay as a result. GP surgeries in the local area were advised to only book in the most urgent patient cases, and, though the worst of the problem is now resolved, frustrations may remain for both patients and staff.

Stories of delays and complications in digital adoption are sure to fuel worry across the field, but do the positives of this technology outweigh the risks? One such instance can be seen through researchers at the University of Cambridge, who present an AI tool that predicts progress of Alzheimer’s disease. This machine learning model proved almost three times more accurate at predicting Alzheimer’s disease progression than current methods, which could significantly improve clinical diagnostic accuracy.

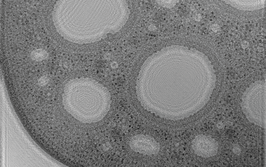

We’ve also seen the benefits of this technology in optimizing image data. A new microscopy method, dubbed APIC (Angular Ptychographic Imaging with Closed-form method), expands on the benefits of Fourier ptychographic microscopy with the adoption of AI. Researchers explain that, “APIC’s analyticity is particularly important in a range of exacting applications, such as digital pathology, where even minor errors are not tolerable.” With new technologies like APIC in development, we could see an AI revolution in the pathology lab.

In oncology, the applications of AI are particularly exciting. One recent study showcased the potential of an AI model for identifying different stages of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) – a preinvasive tumor that can progress into breast cancer. By training and testing this AI model with large datasets of tissue images, it’s capable of streamlining diagnostics and even identifying patients five years before their tumors develop.

The Pathologist Presents:

Enjoying yourself? There's plenty more where that came from! Our weekly Newsletter brings you the most popular stories as they unfold, chosen by our fantastic Editorial team!

Another study has identified potential for deep learning AI in personalized clinical care – specifically in predicting homologous recombination deficiency (HRD). Researchers are confident that this technology, “can predict HRD in breast and ovarian cancers directly from routine H&E slides across multiple external cohorts, slide scanners, and tissue fixation variables.”

As pathologists continue to battle against high workloads while staff numbers are dwindling, the incorporation of AI and digital pathology could support the lab in more ways than one – from improving accuracy, speeding up the diagnostic process, and relieving overworked staff from monotonous tasks. Of course, many clinicians worry about AI replacing their roles in the lab. With technology continuing to exceed expectations and perform at high standards, who would choose physical employees over automated machinery?

To put minds at ease, researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) decided to put AI to the test in regards to medical decision-making. But the results remain inconclusive. When presented with a medical quiz designed to test health professionals ability to diagnose patients, the AI model showed high accuracy in its responses, but struggled to explain its decision making.

“Our research also identified image comprehension as the greatest challenge for GPT-4V, with an error rate of over 20 percent, while medical knowledge recall was the most reliable. This suggests that comprehensive evaluations beyond mere multi-choice accuracy are needed before these models can be integrated into clinical practices,” the study concluded.

With these results, I think it’s safe to say that clinicians jobs are safe in labs across the world. The evolution of AI and machine learning surely cannot take away from the forward thinking and training of a medical professional. However, these examples beg the question: are we rushing headfirst into a digital embrace without considering the consequences – or is this simply a minor wobble at the beginning of a wondrous new relationship? Let us know your thoughts: [email protected]

Deputy Editor, The Pathologist