When Lija Joseph, Chief of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Lowell General Hospital in Massachusetts, acted on a patient’s request to see what her cancer looked like, it sparked the seeds of a practice model that could prove transformative.

Two years later, in 2019, Joseph had established a structured, weekly pathology clinic at Lowell, with buy-in from the hospital C-suite and participation from all the pathologists in the department.

The benefits were striking:

Patients reported improved understanding of their disease and diagnostic process after meeting with a pathologist.

Oncologists and surgeons observed that clinical encounters with better informed patients could focus on treatment planning rather than report interpretation.

Administrators noted enhanced patient retention, greater satisfaction, and fewer communication-related complaints.

Pathologists described a renewed connection to the clinical purpose of their work.

Joseph decided to share the model she had created so that other institutions could follow Lowell’s lead and establish structured patient–pathologist consultation programs. Her first publication on the subject was entitled Please Help Me See the Dragon I Am Slaying – inspired by a comment from one of the patients she had consulted.

As momentum grew, and more pathology departments followed Lowell’s lead, Joseph recognized the need for standardization. Seeking formal guidelines for establishing and running a pathology clinic, she consulted her friend, Michele Mitchell, patient advocate and ASCP Patient Champion.

Mitchell picks up the story:

“Lija Joseph and I had often discussed the value of creating a formal certification program. We believed this would legitimize the concept and support pathologists who were willing to establish and sustain the model of meeting directly with patients.

“I posed the idea to Jeff Myers, the ASCP Patient Champion Chair, who encouraged me to present it to the Patient Champion Steering Committee. They accepted the proposal, funded the effort, and engaged me, Lija, her co-collaborators, and additional contributors in a working group.

“It took about a year for all of us to develop and refine the content, which is now available as the ASCP Pathology Clinics Certification Program. The seven-module resource provides administrative, billing, and communication frameworks for institutions seeking to implement patient-facing programs.

“It’s really great work, and I am so grateful to have been a part of it!”

Kenechukwu Ojukwu – a member of the ASCP working group – is similarly enthusiastic about the program. “This ASCP pathway will give pathologists the confidence, skills, and standardized training needed to engage directly with patients,” she says. “It ensures that pathologist-patient interactions are thoughtful, equitable, and grounded in best practices, ultimately improving communication and expanding access to this innovative model of care.”

Fellow contributor David Li launched his own clinic after his mother's cancer diagnosis and learning that he also carries the BRCA2 mutation. His experience fuels a deep, personal commitment to pathologist-patient conversations. He is confident that the ASCP program will help the growth of pathology clinics. “When I first started doing pathology clinics, I had no real resources other than few articles,” he says. “I had to reach out directly to another pathologist for help. With the ASCP certification pathway, anyone can get started right away.”

John Groth – a pathologist, cancer survivor, and working group member – can also appreciate the value of this work from both sides of the desk. “Pathology clinics create a unique space for patients to see their images, ask questions, and truly understand their diagnosis with the physician who knows their tissue best,” he says. “As a patient, I have benefitted enormously; as a pathologist, I see them as essential to modern, patient-centered care.”

Now, with guidelines in place and a growing body of evidence supporting patient-facing pathology, the stage is set for pathology to redefine itself as a more visible player in the patient journey.

But what do pathology clinics really mean to the patients who visit them? The Pathologist reached out to cancer survivors to ask how a conversation with a pathologist changed the experience of their disease. Here are their stories.

Michele Mitchell’s story

“When I was diagnosed with breast cancer – invasive ductal carcinoma – in 2006, pathology findings were not routinely shared with patients. In my case, it was the medical oncologist, not the pathologist, who told me about my disease. I never saw my pathology report or the slides. I had no visual connection to the cancer that had changed my life.

“I was told it was 'no big deal' because it was Stage 1A – caught early and small (0.9 cm). But something inside me felt uneasy. I realized I didn’t truly understand what had been found inside my own breast. That lack of clarity stayed with me.

“Eleven years later, I learned that patients could actually meet with a pathologist to review their own diagnosis. The opportunity for direct understanding and transparency motivated me to participate in a pathology clinic, seeking clarity and the chance to take ownership of my care.

“During my visit, the pathologist didn’t just review my report – he put my cancer up on the screen as a digital representation. He showed me what normal breast tissue looked like and compared it with my tissue.

“He explained that, for breast cancer, there are only three grades, and then began counting the 'black dots' – the nuclei that determine tumor grade. That’s when I learned that I had a Grade 2 tumor – more aggressive than I had imagined.

“Seeing my invasive ductal carcinoma – 'my cancer' – in this way made the diagnosis real in a way that words never had. I thought about the cancer cells that could still be circulating in my body and potentially metastasize in the future.

“The encounter was not what I expected, but in a healthcare system often filled with starched white coats, confusing medical terminology, and alphabet soup, this pathologist added warmth, clarity, and humanity to my experience. It was transformative.

“I printed the digitized representation of my cancer and keep it on my bedside table. I lost over 100 pounds, began exercising regularly to reduce inflammation, and changed my eating habits. Armed with this knowledge, I feel a sense of control over my disease and now understand what I can do to help keep the “enemy at bay.”

“The pathology clinic transformed my relationship with my care. I became an active participant in decision-making, able to ask informed questions and understand the rationale behind treatment recommendations.

“This experience also shaped my advocacy journey. For the past 14 years, I’ve worked to make pathology patient-centered. I partnered with Lija Joseph to explore creating a formal certification program for pathologist-led clinics.

“I wrote several key sections of the workshop – covering the CURES Act, patient impacts, and the value of partnering with patients to advance pathology – and also recorded voiceovers, sharing my own lived experience with cancer. Throughout the seven modules, additional patient stories are woven in, adding a real and human dimension to the educational experience.

“I am so proud – not only to have brought the concept to ASCP, but to have been an active contributor helping to bring this workshop to life.

“I hold no formal power, but I do have a voice – and I will continue to use it until every patient can see, and every pathologist remembers, the life behind the slide.”

Nancy Wetherell’s story

“I am a 58-year-old patient with atypical hyperplasia, who has been having mammograms, ultrasounds, and biopsies since the age of 30 due to strong family history. In 2019, I had another suspicious area that had been biopsied. Having worked in the lab with Lija Joseph, I approached her with my concerns. She told me about this new Pathology Patient Consult program that she was starting for her patients at Lowell General Hospital and asked if I wanted to participate.

“During the consultation, Dr Joseph discussed the process of staining the slides and explained what we would be looking at. Using a double-headed microscope, we viewed normal breast tissue cells, then compared them with my slides from biopsies taken in 2013 and 2019. I was able to see how my own cells are changing morphologically – flattening and lining up.

“I felt more confident after my consult with Dr Joseph. I was relieved to know that another skilled physician was on my care team. The fear and anxiety about my condition were replaced by positive energy and motivation. As a visual learner, being able to see my own cells was inspiring me to investigate and learn more about prevention and healthy habits.

“Visualizing the changes to my cells reminds me to keep my weight down, practice yoga, and be more present in moments with family and friends. I cannot control my genetics or risk, but I can make better choices to improve my overall mental and physical health. That additional knowledge leads to power when making life choices.

“My message to healthcare leaders would be: Please make this program available to your patients! You can play a vital part of the team of doctors for each patient by providing visual images and expert information. Patients can then use this data and images during treatments, prayers, or as a motivational technique on their health care journey.”

Eva Grayzel’s story

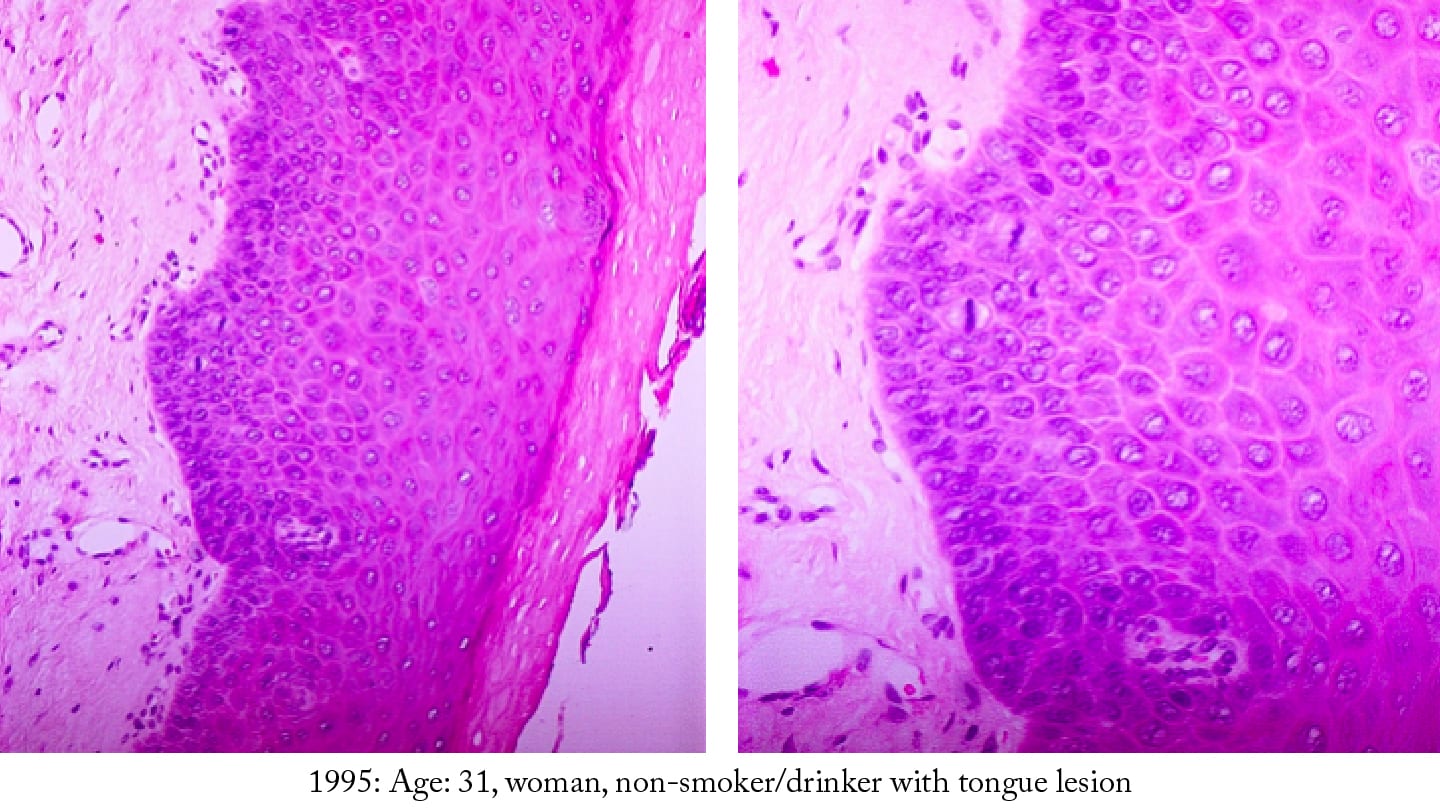

“The first biopsy of the non-healing ulcer on my tongue happened when I was 31. I didn’t even get the results directly — the receptionist called and said, 'You have nothing to worry about.' It never crossed my mind to ask what I should be worrying about. Infection? A virus? Cancer wasn’t even on my radar.

“If I had seen the digitized slide of my biopsy, it would have opened a world of understanding for an otherwise well-educated woman who knew nothing about oral cancer. Visuals make things real. They make questions surface. I would have immediately wondered, 'Could these cells turn into something dangerous?'

“After surgery, I finally met my head and neck pathologist in person. She apologized, explaining that my biopsy had been misread 2 years earlier. It wasn’t hyperkeratosis – it was moderate dysplasia with a real chance of progressing to cancer.

“Had an oral pathologist examined the biopsy instead of a general pathologist, I would have been diagnosed early, not late. I would have been spared the lifelong effects of treatment. Today, as a 27-year survivor, I manage the fallout every day.

“Now, when someone tells me they’re having a biopsy, I make sure they know about pathology specialists. Most patients have no clue. And if something in a report doesn’t make sense, I say, 'Call the pathologist.' Truly – it can only help.

“Pathologists aren’t always used to talking directly with patients, and that needs to evolve. Given the right training in plain-language communication, they could empower patients instead of leaving them in the dark.”

Deedee O’Brien’s story

“I was diagnosed with, and treated for, renal cell carcinoma in 2008, a brain meningioma in 2009, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in 2016 – which I live with today. With the CLL diagnosis, I was invited to be one of the first Patient Champions for the American Society for Clinical Pathology and as such was introduced to my pathologist for the first time.

“When I met with my pathologist at Beth Israel in Boston in 2017, she showed me my slides going back to 2013, when she first saw the changes in my cells that would become CLL. I was amazed! Seeing my own cells changing year over year until I was finally given the diagnosis in 2016 was surprising and daunting. I had no idea this was happening within my body and how life-changing it would become. To know someone was in the lab watching these changes and predicting their meaning was mind-boggling.

“My first response to this new knowledge was quite emotional. The realization that my body was going through changes beyond my control left me bewildered and then sparked curiosity – and determination. Being able to speak with my pathologist about this as she showed me the increase in cell mutations year over year put my disease into perspective. It was real. Now that I could see it and understand it, curiosity developed, and I wanted to learn everything I could about it.

“That experience taught me the questions to ask and gave me the courage to ask them. It also influenced me in my role as a caregiver. I no longer just accepted the initial diagnoses regarding my loved ones, but learned to seek the bottom-line truths, the options, and the opportunities for the best possible paths to follow.

“Without such knowledge the patient journey can be confusing and frightening. But with the support of a medical team that works for and with the patient – the patient can face anything with the confidence that everything that can be done is being done. The pathologist is the foundation and catalyst for that all-important confidence!”