Developing countries continue to face significant workforce shortages – particularly pathologists – which causes long delays in diagnosis and overburdened healthcare systems. In hopes of improving these services, The Pathology Network (TPN) was created: bringing together a global network of pathologists to support clinical shortages. To learn more about this initiative, we spoke with TPN Founder Joshua Kibera.

Was pathology what you expected it to be when you graduated/took your first job? Why – what was different?

Medical school shaped my view of pathology. I learned that it was the scientific foundation of modern medicine and essential to understanding diseases. During my surgical rotation at a faith-based hospital near Nairobi, my supervisor sent me to the pathology lab. I walked through the hospital corridors and into the lab, where I was directed to a small office in the corner.

When I knocked, two friendly voices invited me in. Inside, the aroma of coffee filled the air, and golden sunlight streamed through a large window overlooking forested hills. Books lined the shelves, and two elderly volunteer pathologists from the United States welcomed me with coffee and a seat. As we discussed a case, I couldn’t help but notice the contrast between surgery and pathology. Pathology felt more inviting – full of knowledge, patience, and a willingness to teach. At that moment, I could see myself in their place. That was the beginning of my journey into pathology.

This culture of learning continued during my residency at Aga Khan University in Nairobi, a leading institution dedicated to improving medical education in Africa. Since 2005, the university has invested millions in postgraduate education across Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. As a beneficiary, I trained with advanced equipment and techniques unavailable in most regional pathology programs at the time.

However, the real world was different from the idealized version of pathology I had known. The institutions I worked for lacked significant investment, and there were too few pathologists to foster a strong pathology culture. I took a teaching position at a medical school in a rural Kenyan town, four hours from Nairobi. I was only the second pathologist in town and the only histopathologist – but there was no histopathology lab. Surgeons sent samples to Nairobi for testing, allowing middlemen to exploit both doctors and patients. The quality of results varied widely, and many local physicians appeared to have lost faith in pathology.

My vision of practicing in a well-equipped lab, surrounded by books and the smell of coffee, quickly faded. There was no office, no lab, and no coffee – my employer preferred tea. My dream of specializing in a particular area of pathology had to wait. Before anything else, there was critical work to be done: building the infrastructure and systems needed for quality pathology practice.

What inspired this project?

Several experiences in 2015 and 2016 inspired the creation of TPN, but one patient in particular left a lasting impact and made me rethink my practice.

Martha (name changed for privacy), a 45-year-old farmer living 60 km from town, was referred to a fine-needle aspiration clinic at a hospital where I volunteered once a week. When she arrived, I discovered she had an ulcerated lump the size of a tennis ball in her left breast – stage 4 breast cancer. As she shared her story, it was heartbreaking to realize how the system had failed her.

A year earlier, when her lump was still small, she sought medical help. It took two months to perform a biopsy, which she believed was a surgery to remove the tumor. She was told to send the sample to Nairobi, nearly 300 km away, for testing. She did everything right – took the sample to a private lab, paid the fees, and went home. A month later, the results were ready, but no one informed her. She only returned to the hospital a year later when the lump "recurred" as a non-healing ulcer. She had no idea she had cancer.

This was a tragedy. Martha followed all medical instructions, and the hospital had the necessary resources to diagnose her. Yet, a lack of coordination between her, her doctors, and the pathology lab turned a treatable cancer into a palliative case. In that lost year, her five-year survival chances dropped from 90 percent to less than 30 percent. That was my wake-up call – a better lab alone would not fix this problem; the solution had to be broader and systemic.

Martha’s story taught me that skilled specialists and advanced equipment are not enough. A functional healthcare system requires timely, accurate communication and coordination among all involved. Only then can we eliminate inefficiencies and give patients the best chance at a positive outcome.

Please tell us about your novel workflow.

With only one pathologist for every one million Africans, diagnosing diseases in Africa is challenging. The process involves multiple people across vast distances and different institutions. Hospitals and doctors usually handle tissue sample logistics, payments, and result follow-ups themselves. In some cases, like Martha’s, patients are given their samples and told to return with the results later. There is no standardized system, leading to major delays in diagnosis.

My team and I realized the solution was a single diagnostic platform to coordinate the entire process – from patients to pathologists and back to clinicians.

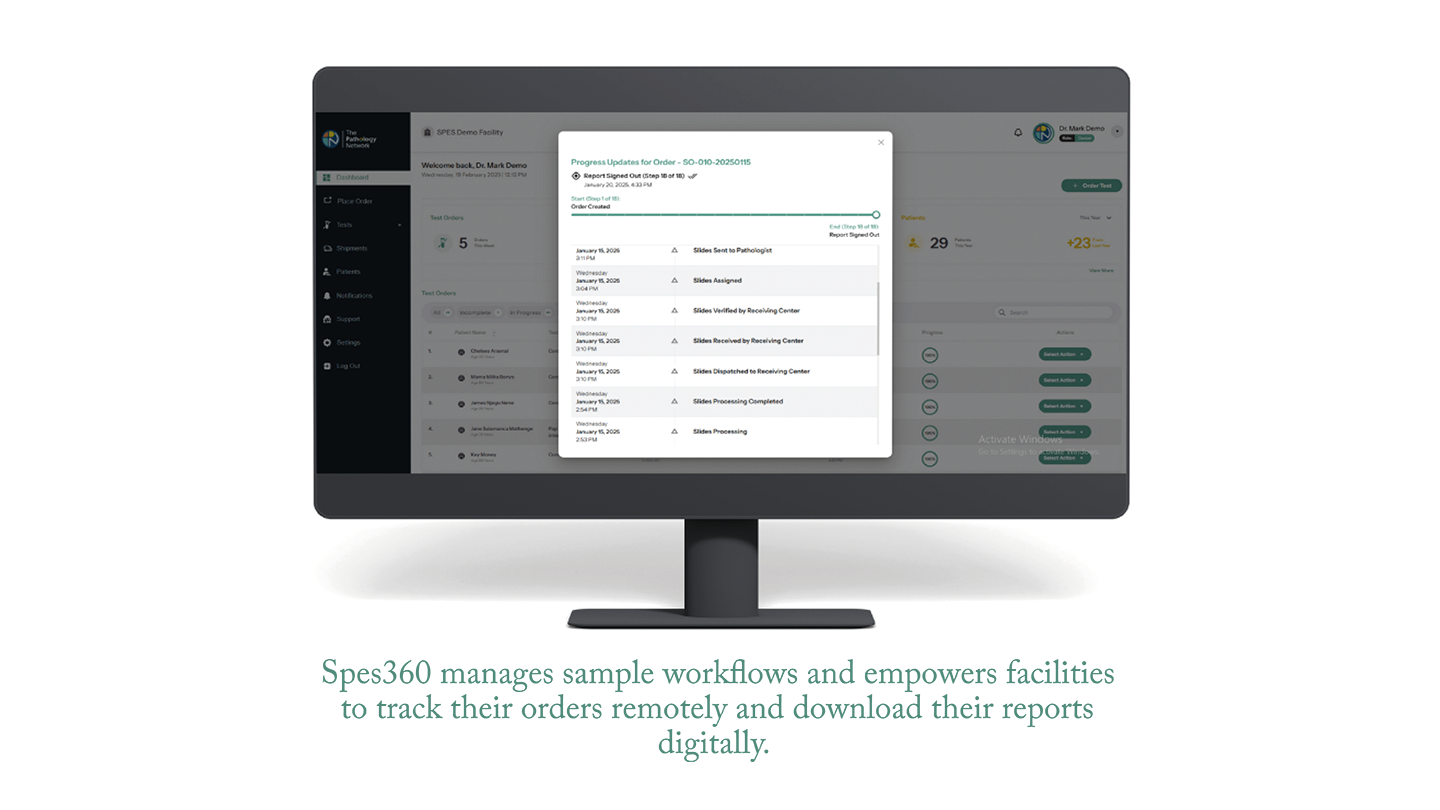

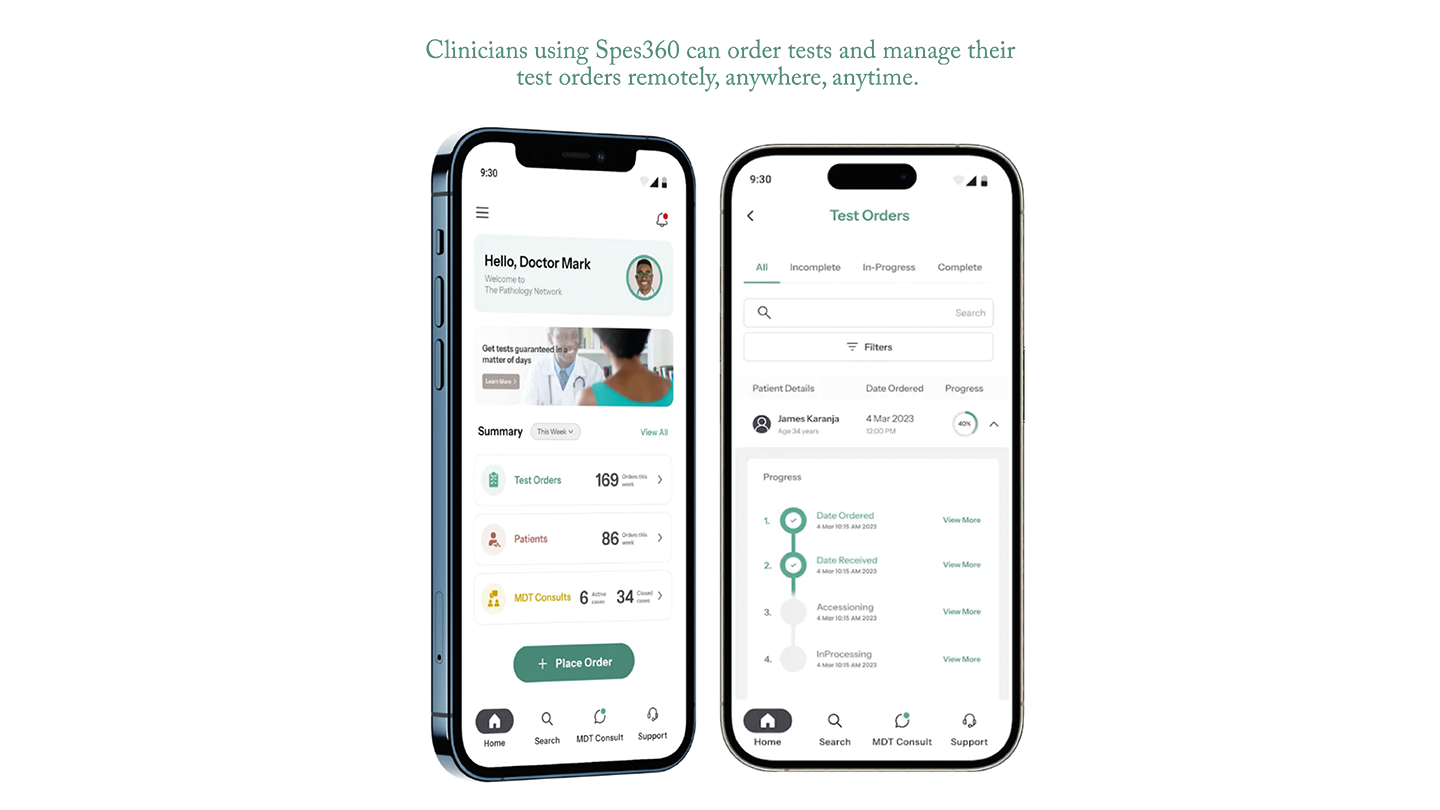

We created the Spes360 Diagnostic Management System, an online platform designed for Africa and beyond. It centralizes coordination of the diagnostic process across institutions and countries. Hospitals and doctors order tests through us, and we manage everything from sample transportation, sample testing, and quality control to pricing and turnaround time. A network of 14 remote pathologists reports results virtually, reducing biopsy turnaround time in Kenya from a national average of 30 days to just 7 days – in contrast to Martha’s one-year wait.

When results are ready, the pathologist – often working remotely – releases them digitally, and the patient gets a text message notifying them to return to their doctor. This system makes diagnostics predictable and safe, ensuring proper coordination and communication for better healthcare.

We aim to expand this system across Africa and other developing regions. By optimizing limited pathology resources and integrating AI, we believe we can transform healthcare outcomes, particularly for non-communicable diseases like cancer.

What roles do artificial intelligence or machine learning algorithms play in your workflow?

Our role in managing sample workflows – from hundreds of doctors to central labs and partner pathologists – means we constantly handle logistical and communication challenges.

To improve efficiency, we use AI to assign support tickets to the most available and skilled customer service or logistics officers. AI also analyzes our workflow and suggests improvements. We are now exploring AI/ML integration into our Spes360 software to assist doctors in ordering tests and help pathologists with reporting.

How does this approach differ from existing digital pathology workflows, especially in terms of scalability and cost-effectiveness?

Our digital pathology workflow is designed specifically for the African medical landscape and is constantly evolving. It is modular and flexible, supporting both centralized scanning – where multiple labs share high-volume scanners – and decentralized scanning, where low-volume scanners connect remotely to a central image server through Spes360.

We use Spes360 to distribute cases to partner pathologists, who can remotely view slides and generate reports using a browser-based viewer. To reduce costs, we leverage cloud-based storage, automatically shifting images from expensive high-access storage to more affordable low-access storage.

Our system is built for flexibility, scalability, and compliance with national regulations. We are continually developing secure ways to expand digital pathology to patients in developing nations who need it most.

What types of pathology services or diagnoses are most suitable for this workflow, and why?

Our workflow is sample agnostic. Originally built to connect patients with specialists in histopathology, cytopathology, and hematology, it can be easily adapted for other tests. Spes360 manages the entire process – from test ordering and sample logistics to processing and reporting – making it versatile across various medical fields. Recently, we successfully adapted it for national HPV screening, proving its flexibility and reliability.

Did you face any challenges while developing TPN and if so, how did you overcome them?

The goal of TPN – creating a unified platform to connect clinicians with remote pathologists and improve Africa’s diagnostic efficiency – initially seemed overwhelming. It was technically complex, financially daunting, legally challenging, and socially uncertain. Perhaps that’s why no one had attempted it before.

When I began developing the first version of our software, later named ALIS, I was well aware of Africa’s pathology challenges. My experiences shaped this understanding: five years as an undergraduate in Uganda exposed me to a different healthcare system and culture, while growing up in 1990s Kenya meant hearing firsthand accounts of conflicts in Somalia, Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and South Sudan. Later, as a professional, I studied how this instability devastated healthcare systems.

At first, my goal was simple: build a software tool for pathologists and labs to use within their own countries, adapting it to local needs. It was meant to function like a specialized LIS, helping solo-practice pathologists connect with clients and colleagues using digital pathology. But early experiences showed me this approach was flawed. It wouldn’t help patients like Martha in countries with no pathologists at all.

It also became clear that ALIS couldn’t scale beyond Kenya without significant funding and structural support. To build software for multiple markets, we needed external investors and co-founders. Between 2019 and 2021, recruiting co-founders and starting the fundraising journey was one of our most educational experiences. It helped us refine our understanding of the problem and improve our solution. Though fundraising was slow, our small team celebrated each milestone along the way.

Looking back, I’m grateful for the challenges, tough questions, and setbacks. Without them, we wouldn’t have the solution we have today – one ready to serve the entire continent.

How do you address concerns about data privacy, especially when dealing with patient information in low-resource settings?

We take data privacy and sovereignty very seriously, ensuring that African health data is protected, controlled locally, and benefits African patients. Our solution complies with Kenya’s data laws, as well as HIPAA and GDPR standards. We are also working on FHIR standards for interoperability.

The Spes360 DMS is designed to make digital pathology affordable in developing countries without compromising data security. It also allows customization to meet the legal and national requirements of any country we expand to in the future.

What are your hopes and plans for the future?

We believe AI can help bridge Africa’s massive diagnostic gap. A study estimated that, at the current rate of training, it would take 400 years to have enough pathologists for the continent. Our bold vision is to create a post-AI diagnostic future, allowing Africa to leapfrog traditional diagnostic workflows used in developed nations.

By combining AI-powered diagnostic tools with our logistics and quality control systems, we can transform existing African pathologists into "super pathologists." These tools will help them diagnose rare cases more accurately, manage overwhelming workloads, and train the next generation of pathologists.

Beyond Africa, our Spes360 DMS fosters global collaboration. It enables developing countries to share pathologists across borders, allowing nations like Burundi to access expertise from regional pathologists in Kenya, Tanzania, or Uganda at an affordable cost.

Our system also facilitates North-South cooperation, connecting patients with global experts for specialized support. Additionally, it allows African pathologists in the diaspora to contribute remotely to their home countries.

We are excited to expand this system beyond Africa to other regions in need. Our mission is clear – we will continue to develop and deploy the tools that pathologists in developing countries need to improve diagnostic access, speed, and quality for their patients.

The Pathology Network is a healthtech companynow headquartered in Oxford, UK, with support from the UK’s Global Entrepreneur Programme. We are actively looking for partners, collaborators, and investors to help expand this vision across Africa and beyond.

Image Credit: Titus O'Connor