Textbook-altering research has revealed lymphatic vessels that directly connect the brain and the immune system

For decades, researchers have posited theories as to how the brain affects the immune system, ranging from afferent nerve pathways to neuropeptide receptors on lymphocytes. The one theory that has always been discounted is the presence of a direct lymphatic vessel connection between the brain and the immune system – and that’s exactly what researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine (Charlottesville, VA, USA) have just discovered.

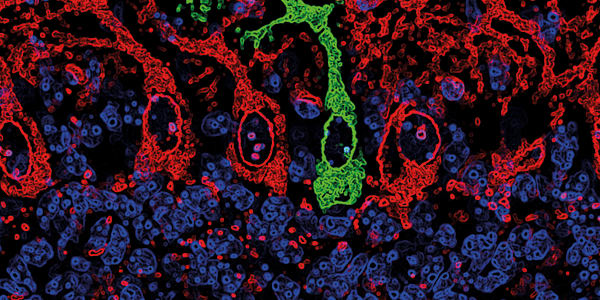

The lymphatic system has been extensively mapped using a variety of techniques, but these vessels, which line the dural sinuses, have never been detected before – possibly due to their unique location. Fortunately, postdoctoral fellow Antoine Louveau was trying to find out how T cells get into and out of the meninges, so he developed an immunohistochemistry technique that involves fixing whole-mount meninges while they are still attached to the skull cap, then dissecting and examining them (1). It was this technique that allowed the vessels to be spotted for the first time when Louveau’s stains revealed a high concentration of immune cells near the dural sinuses. Noticing the vessel-like pattern of distribution, Louveau tested for the lymphatic endothelial cell marker Lyve-1, confirming the presence of two to three Lyve-1-expressing vessels that run parallel to the dural sinuses and are not part of the cardiovascular system. In a press release from the University of Virginia (2), principal investigator Jonathan Kipnis said, “I really did not believe there are structures in the body that we are not aware of. I thought the body was mapped.” He believes that the lymphatic vessels are so close to a major blood vessel in the same area that they have previously been overlooked. Kevin Lee, chair of the Department of Neuroscience, added, “The first time these guys showed me the basic result, I just said one sentence: ‘They’ll have to change the textbooks.’”

The meningeal vessels are characteristic of initial lymphatics, which collect lymph from the interstitial fluid. But they also possess some unique features – the vessels are smaller and cover less total tissue area than most, starting from both eyes and traveling past the olfactory bulb to the sinuses. Injecting dye into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed that the meningeal lymphatic vessels are involved in CSF drainage from the ventricles; immunohistochemical staining revealed that they also provide passage for immune cells. Previous studies have shown that CSF elicits an immune response in cervical lymph nodes, a function whose proposed pathway runs via the nasal mucosa. Using dye to trace the passage of fluid from the ventricles to the deep cervical lymph nodes, Louveau and his colleagues suggested that lymphatic vessels in the meninges, rather than in the nasal mucosa, are the primary drainage route for CSF components. But the real question is: what significance will this discovery have on the study and treatment of neurological diseases? Kipnis thinks the implications are far-reaching. “We will be able to better study neuro-immune communication in healthy and diseased brains,” he says, highlighting the novel ability to conduct mechanistic studies on the brain’s immune responses. He and his colleagues believe these vessels may be involved in neurological conditions from autism to multiple sclerosis – an example he gave was Alzheimer’s disease, in which protein accumulation in the brain may be caused by inadequate meningeal lymphatic drainage. One thing is certain: any researcher who studies a neurological disease with immune system involvement should be very interested in this new discovery.

References

- A Louveau, et al., “Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels”, Nature, [Epub ahead of print] (2015). PMID: 26030524. J Barney, et al., “Researchers find textbook-altering link between brain, immune system” (2015). Available at: http://bit.ly/1EZss5X. Accessed June 9, 2015.