Want to hear this article in Michele’s own words? Click here to watch the videos of the interview!

In 2006, I was diagnosed with breast cancer.

I received the tentative diagnosis at work. That day, I went home and told Ray, my husband of less than a year. He agreed to help me in my fight – but, just half an hour later, Ray had a stroke. A month later, I took him off life support. One week after burying him, I began my battle with breast cancer.

I was treated at the University of Michigan’s Comprehensive Cancer Center. My treatment plan included a lumpectomy surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, an additional surgery, and years of anti-hormonal “pills.” I am now in remission – having completed the final phase of my treatment plan in 2015 – but, like many cancer survivors, I still suffer from the side effects of treatment and I continue to struggle with thoughts of recurrence. A cancer journey is a lifelong marathon, not a sprint.

How it began

Waiting for the results of my biopsy was agonizing. It took two weeks. I couldn’t sleep or eat; I worried every hour of every day. Ray was in intensive care. I wondered, if he lived, how would I care for him and manage my own breast cancer journey at the same time? What would my life be like? I wanted to get the tumor out of me. Finally, my oncologist called with the results of my core needle biopsy, which confirmed the ultrasound report from weeks earlier. It was a “malignancy.” I heard the words “breast cancer” – and then my mind went somewhere else. I was numb. I had so much on my plate at that point that the news was totally overwhelming.

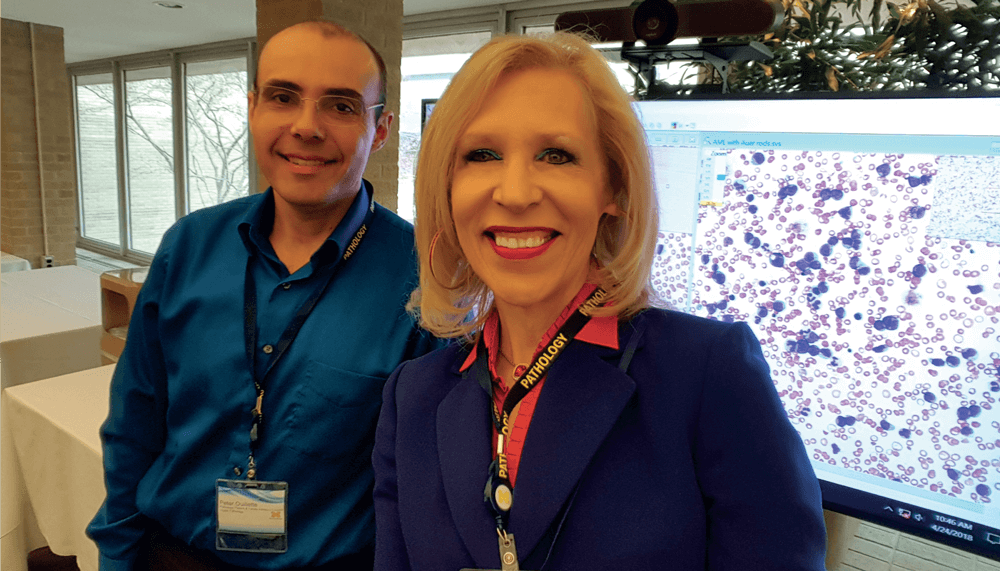

I still remember the day I decided I wanted to look at my own pathology slides. I already had the honor of being a patient advisor and the co-chair of UMich Pathology’s Patient and Family Advisory Council. The chair of the committee, a pathologist, offered to show me my cancer and review my pathology report. At this point, it had been 10 years since my diagnosis and one year since I had completed my treatment plan.

What made me curious? When I was diagnosed, I never saw my pathology report or slides. I was told that my breast cancer had been caught early. What I knew was that I had an invasive ductal carcinoma with no lymph node involvement. It was stage I and small – 0.9 cm. My oncologist said my prognosis looked “good.” Over the years, I had done a lot of research on my own – but I still had a lot of questions and looked forward to learning more.

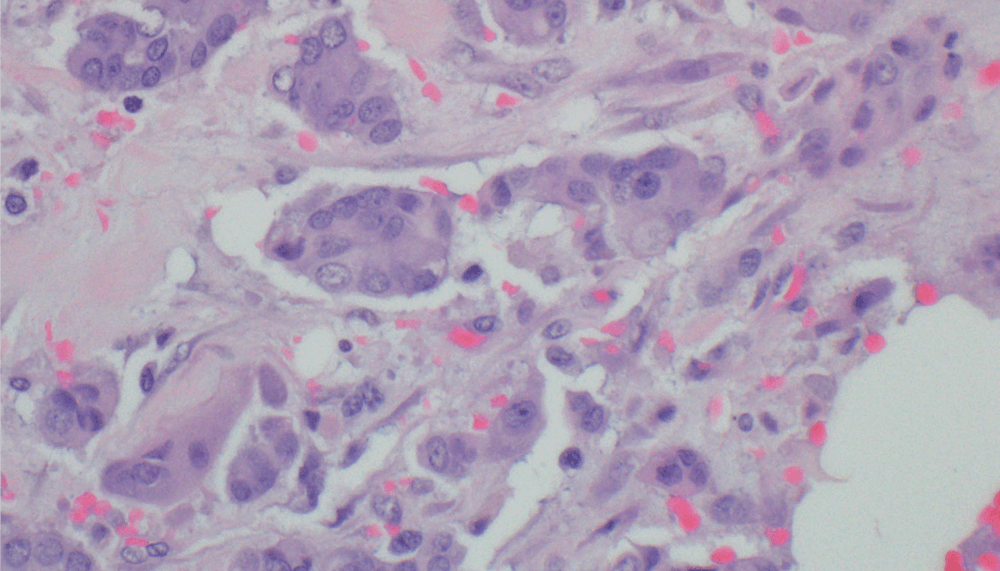

First, the pathologist showed me “normal” tissue. Next, he put a digital slide of my tumor on the screen. He explained how they stained the slides and determined the tumor’s characteristics. My tumor was “luminal A” (ER/PR+, HER2-). He explained how they determined the grade of the tumor. I had never heard of tumor grading before. I thought, “Wait a minute – I had a stage I tumor. What’s a ‘grade?’” My pathologist explained that the black dots I saw on the screen were cancer cells. He said they count the number of cancer cells to determine the grade of the tumor and that the grade defines the tumor’s aggressiveness. I had a grade II tumor, which tend to grow more quickly and are more likely to spread to other parts of the body. My mind raced. My cancer was invasive and there are only three grades – so my breast cancer was more aggressive than I had previously understood.

I was clearly upset by this news, so we stopped for a moment so that I could process the information. The sheer “size of the enemy” is what stays with me from that experience. It has been 16 years and I still wonder whether some of those cancer cells are floating around in my body. Although it was not what I expected, I am grateful for the compassionate way the pathologist handled the visit. The encounter extended a warm touch in a world filled with barcodes, sterile instruments, and starched white coats.

From patient to advocate

I retired from my 25-year career with a large healthcare insurer in 2009. At that point, my desire for patient advocacy work led me straight to the University of Michigan healthcare system. I also serve as an advocate for the American Society for Clinical Pathology and for the American Cancer Society. I am honored and privileged to serve each of these institutions. It feels wonderful to educate and empower patients, move the needle on important issues, and make a real difference in policy, quality, and safety in health care. I view my efforts through the lens of a quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson – “The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well.”

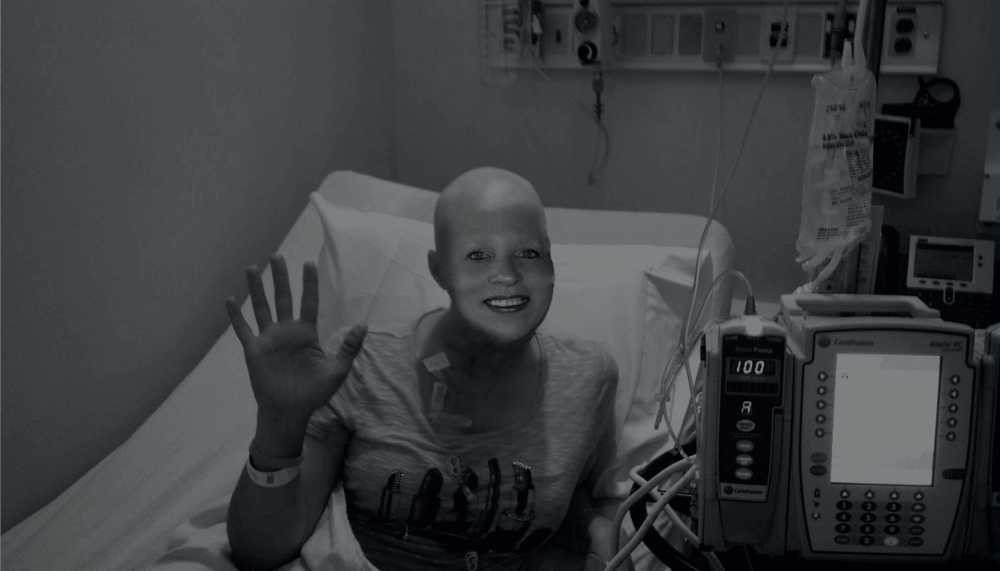

I’m no stranger to advocacy – not just for myself, but for others as well. In 2013, my stepdaughter, Tricia, lost her three-and-a-half-year battle with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Tricia had asked for my support on her journey and my help navigating health systems. We tried desperately to get her well – but even experimental treatments failed. She died at the tender age of 23. Next, my parents had open heart surgery 11 days apart. My Dad’s lungs never recovered after surgery and he passed away in 2014. My mother’s health failed shortly thereafter. She had pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure. We lost Mom in 2019. In 2016, my husband, Bill, had a melanoma recurrence and we discovered that he carries a MITF gene mutation that predisposes him to melanoma and renal cancer. In my role as caregiver, I helped family navigate healthcare systems, which can be challenging. My path was made clear; these experiences ignited a fire within me to pursue patient advocacy.

You can see how much pathology and laboratory medicine have touched my life – and how much they touch every patient’s life.

Advocacy challenges

I think it is important to understand the history of advocacy in the US healthcare system. The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey program over a decade ago highlighted the importance of high-quality patient- and family-centered care. HCAHPS survey results are used in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Value-Based Purchasing program and affect hospital reimbursement by up to 25 percent – so hospitals are motivated to achieve. Patient- and family-centered care should involve working with patients and families, rather than just working for them or doing something to them. I have witnessed some progress over the years to move from doing things on behalf of patients towards doing things in conjunction with patients – but, in my opinion, the pace is too slow.

I would love to reframe the role of councils in healthcare systems everywhere from “advisory” to more action-oriented “transformation” teams. In my experience, hospital staff bring issues to patient advocates, who then provide feedback. I would like to see advocates be given a more active role. I believe this is the next step in the evolution of the movement. Advisors can provide systematic feedback on quality and safety concerns by truly partnering with healthcare systems and organizations – moving from bystander to policymaker. With the advent of personalized medicine, AI, and a more educated patient population, I think patient advocates are ready to make real change.

We’re in an exciting and transformational time. Patients have never had more access to information about their health, including options for maintaining or improving their condition. Medical records are available online, as are patient forums, blogs, and websites. With health records now fully digitized and available on patient portals, action can be instant. At the same time – in part because of the rising costs to individuals – increasing numbers of patients are investing in their health to stay well, not just get well. Health trackers are now the norm rather than the exception. Savvy patients are beginning to understand how unhealthy behavior can impact their pocketbooks in the long run. When patients become ill, they are increasingly focused on learning more through online communities. Advanced digital communication technologies enable the delivery of chronic care at home. A patient’s laptop or mobile device can be a substitute for the doctor’s office through apps and virtual visits – a game-changer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The era of the passive patient is over – and consumers of healthcare will increasingly demand better tools, personalized treatment plans, and multidisciplinary care teams.

A double-edged sword

Patients have a right to their own health information but often need assistance understanding and interpreting it. There is a vast amount of information – and, unfortunately, misinformation – out there. Patients need help to synthesize this information and I think doctors and health systems need to take on an expanded role. Trusted clinicians should provide reputable sites to search, engage in more outreach, and preemptively educate their patients. I love the phrase, “Nothing about me without me.” However, patients must also take more responsibility for their own care. They need to help their providers by engaging in the prescribed treatment plan, asking the right questions, and partnering with their providers in shared decision-making.

The 21st Century Cures Act, which was signed into law in 2016 and updated in December 2020, includes provisions for making pathology reports and laboratory results immediately available to patients via electronic portals to ensure timely access to health information. The College of American Pathologists provides some guidance for how to handle publishing test results, including this note on the new rule: “Pathologists should not delay the release of laboratory and pathology results until the ordering clinician’s review (1).”

Some pathology practices have responded with a great deal of anxiety; others have risen to the opportunity by rethinking the way they provide results to patients. Some practices have added disclaimers on the patient portal; others have added links to reputable sites on the resources tab so that patients can find trusted information.

Most cancer patients never meet or interact with the pathologist responsible for evaluating their tissue samples to determine the type and stage of their disease. Yet pathologists can impart knowledge about test results and better prepare the patient to participate in their own care. There is a growing movement in pathology to create opportunities for pathologists and patients to interact in what is referred to as “pathologist–patient consultations” or “pathology educational clinics.” I hope that this unique approach to personalized medicine takes off and is offered at many health institutions.

The case for consultations

I think pathologists can offer patients a different perspective on their condition. Showing a newly diagnosed patient their tumor offers them an opportunity to understand how the diagnosis was made and to learn some of the science behind the diagnosis. The pathologist can clarify the diagnostic process, enhance the patient’s overall understanding of the disease, and answer any questions – ideally without inducing “information overload.” There are trailblazers out there doing this work already. For example, Lija Joseph at Lowell General Hospital, who has been conducting pathologist–patient consultation services for breast cancer patients, recently held a webinar that included a step-by-step masterclass in successful patient interactions.

Even for more experienced patients, the ability to ask questions can help decisions about a course of treatment or a clinical trial. Moreover, a conversation with a pathologist can help them understand how their treatment plan is working and offer them some feeling of control over their disease process. Knowledge is power.

There is also plenty of data on how interactions with patients can help pathologists. A recently published article indicated that 86 percent of pathologists were interested in meeting their patients (2). Pathologists identified several benefits, including increased job satisfaction through meaning and purpose. Some have described these encounters as a reason to get up in the morning and called them “the right thing to do.” In addition, it may increase motivation to complete the less interactive parts of their work. Other positives include creating a more multidisciplinary work environment; pathologists have unique expertise and including them in the care team could reduce clinician burden. Pathologists are often referred to as “the doctor’s doctor” – but they can be much more than that. A pathologist can also be the patient’s doctor and a vital part of their care team.

Tips for Institutions

Lessons from UMich on increasing the patient’s role in pathology and laboratory medical care

Patient advisors have been added to patient safety meetings, in which participants perform root cause analyses and examine lessons learned when things go wrong.

The team has completed work on a video project to show what pathology is all about. The 20-minute video takes viewers behind the scenes of Michigan Medicine’s pathology labs with a former leukemia patient now in remission.

Patient advisors attend the Department of Pathology Quality Council and participate on quality panels.

The pathology department has participated in patient experience expos in which members spread the word about the impact of pathology on diagnosis and treatment.

The group is currently working on developing a pilot patient education consultation program focusing on two disease groups: breast cancer and diabetes.

We are addressing the Cures Act by adding a disclaimer to the patient portal and reliable resources for patients to access regarding pathology reports and lab results.

Supporting patient-centered care

What can you do? Well, you can seek out opportunities to engage with patient advocates in your own work environment. There are labs and institutions doing patient education sessions and starting their own patient and family advisory councils. Some trailblazers in patient education consultations have information available on the Internet – from published papers to step-by-step video guides.

To make sure these clinics are sustainable, I believe you must show some benefit in the quality of care, treatment compliance, and increased patient satisfaction – things that could affect the bottom line; for example, you could follow up with patients via surveys or use the messaging tools in patient portals to communicate with them. The pathology report is an important source of information regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, but it can be difficult to understand due to its specialized language. Very few resources are available to help patients read and understand their pathology report.

Personally, I use websites such as mypathologyreport.ca. Developed in collaboration with patients and family members, such resources can be offered as an alternative to or alongside pathologist–patient consultation programs. Notably, there is an option on the site to ask for additional information; I did so and, within a day or so, I received a response with additional links to vetted information. Adding this kind of service or linking to other reputable sites on a resource tab in patient portals can be helpful; after all, patients are already out there Googling…

Interested in starting a patient communication initiative? Here are my top tips:

Find a colleague or ask your department chair to support a small pilot program. Having a champion is key to moving patient education consultations forward.

Social media hashtags like #visiblepathologist are good sources of information and contacts.

Training on how to deliver difficult news is important. I would encourage this type of training for pathologists who want to be involved in patient–pathologist consultations.

Create a video to explain what pathologists do or to explain the sections of the pathology report and what each one means.

Perhaps you can add a patient-friendly section to the pathology report itself. If not, something as simple as adding your phone number or email address to the pathology report lets patients know you are available to them – and could be the start of a larger movement.

The shift toward patient education is forward-thinking and, in my opinion, moves the needle on personalized medicine. These steps begin to transform the healthcare system from doing things to or for patients and toward partnering with them instead. My hope is that, someday, pathologists will be an integral part of a patient’s multidisciplinary care team.

Behind every test, specimen, or result is an anxious, sick, tired, scared person. They are wondering what you are looking at or for. And they are waiting for crucial answers. What does it mean for their future? How will it change their treatment plan? You are the first one seeing that person’s diagnosis, which may be life-altering. It should never be taken for granted.

Finally, to the pathologists and technicians who examined my tumor, stained my slides, and determined that I had clean margins; to the blood draw team who determined whether I could or could not be infused with chemotherapy on a given day; to the countless others who worked on what may have felt like routine tasks at the time, I will be forever grateful to you all. You are the nameless heroes who saved my life.

People illustrations credit: Shutterstock.com

People illustrations credit: Shutterstock.com

References

- College of American Pathologists, “CURES Act Fact Sheet” (2022). Available at: https://capatholo.gy/3qzR3Rt.

- CJ Lapedis et al., “Broadening the scope: a qualitative study of pathologists’ attitudes toward patient-pathologist interactions,” Am J Clin Pathol, 156, 969 (2021). PMID: 33948623.