Click here to download a PDF version of the heat map

Click here to download the raw data PDF

An ever-increasing workload and an insufficiency of pathologists; it’s an old story and we know it well. At least, we think we do – but how many of us know the actual numbers behind this received wisdom? And does the numerical imbalance stay the same from region to region, country to country? The truth is, nobody has ever defined the details of this broadly appreciated, but vaguely understood, narrative of the shortfall in trained pathologists – until now, that is.

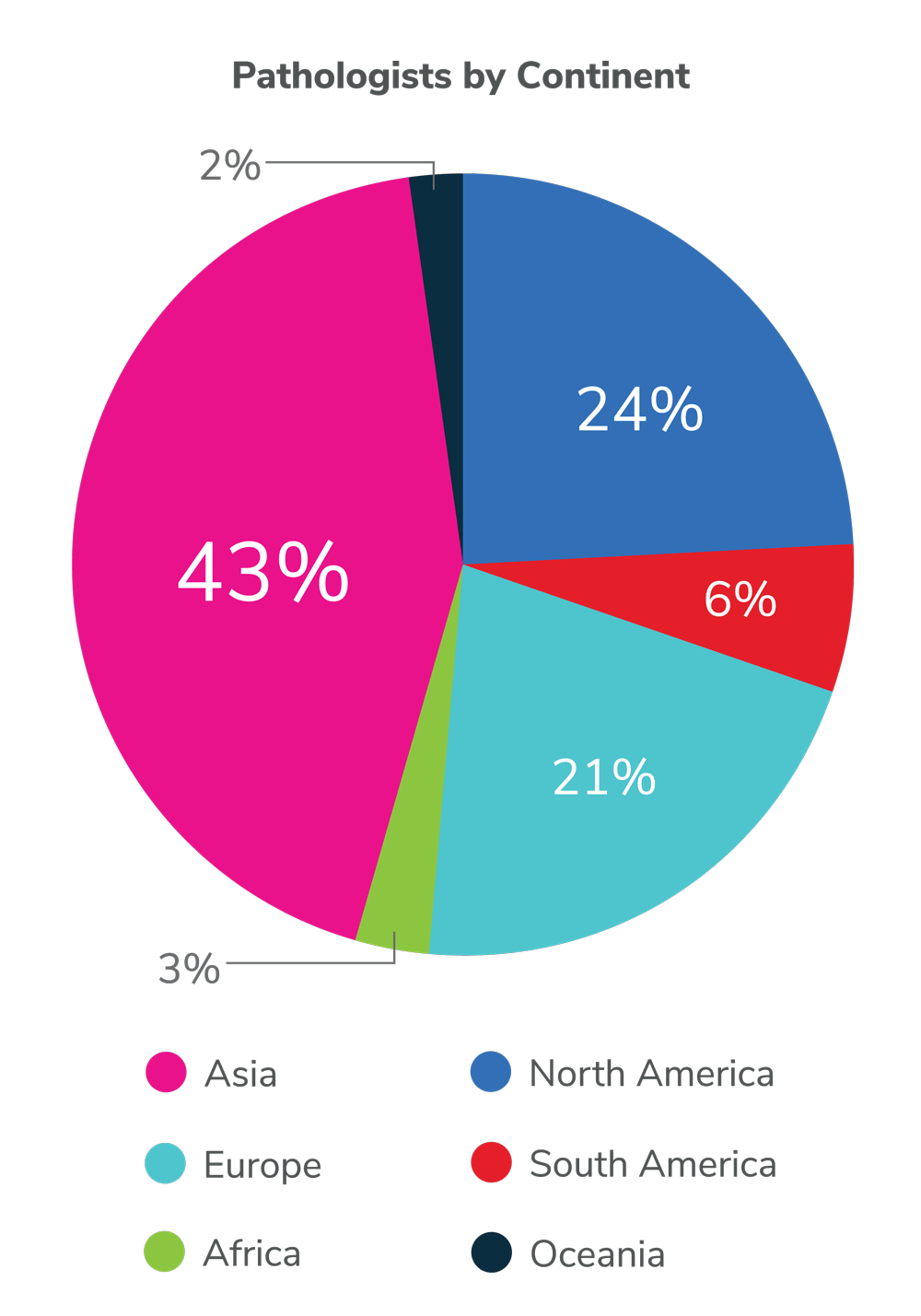

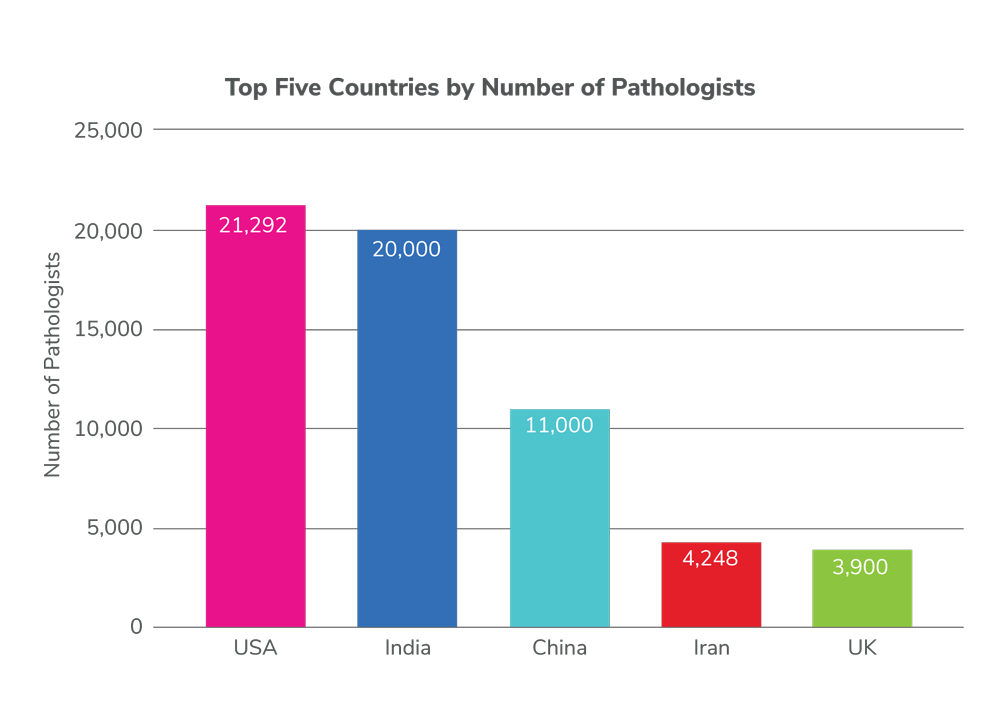

This groundbreaking map represents the first-ever attempt at a global quantification of pathologist numbers: over 108,000 individuals in 162 countries and territories, representing about 98.5 percent of the world’s population (data collected in 2019–2022 by Andrey Bychkov). It also reveals glaring disparities; the mean number of pathologists per million population is 14, but people in the United States enjoy 65 pathologists per million, whereas those in Africa have access to, on average, fewer than three pathologists per million. The 10 countries with the highest number of pathologists account for over two-thirds of the total pathologist workforce worldwide – a list is topped by the US, India, China, Iran, and the UK. Worldwide, the WHO estimates the number of medical doctors at approximately 13.2 million, indicating that about one in every 120 doctors (0.8 percent) is a pathologist.

An ever-increasing workload and an insufficiency of pathologists; it’s an old story and we know it well. At least, we think we do – but how many of us know the actual numbers behind this received wisdom? And does the numerical imbalance stay the same from region to region, country to country? The truth is, nobody has ever defined the details of this broadly appreciated, but vaguely understood, narrative of the shortfall in trained pathologists – until now, that is.

This groundbreaking map represents the first-ever attempt at a global quantification of pathologist numbers: over 108,000 individuals in 162 countries and territories, representing about 98.5 percent of the world’s population (data collected in 2019–2022 by Andrey Bychkov). It also reveals glaring disparities; the mean number of pathologists per million population is 14, but people in the United States enjoy 65 pathologists per million, whereas those in Africa have access to, on average, fewer than three pathologists per million. The 10 countries with the highest number of pathologists account for over two-thirds of the total pathologist workforce worldwide – a list is topped by the US, India, China, Iran, and the UK. Worldwide, the WHO estimates the number of medical doctors at approximately 13.2 million, indicating that about one in every 120 doctors (0.8 percent) is a pathologist.

Quantifying the problem in this way is essential, but represents only part of the value provided by these data; crucially, they provide a baseline for future investigation and may help direct personnel recruitment plans in countries across the globe. In brief, they represent an essential first step in correcting the significant international imbalances in pathologist supply.

Our Panelists

Stanley Robboy is Professor Emeritus of Pathology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Stanley Robboy is Professor Emeritus of Pathology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Bruno Märkl is Director of the Institute for Pathology and Molecular Diagnostics, University Medical Center, Augsburg, Germany.

Bruno Märkl is Director of the Institute for Pathology and Molecular Diagnostics, University Medical Center, Augsburg, Germany.

René Buesa is retired; formerly Histotechnologist and Pathology Laboratory Manager at Mount Sinai Medical Center of Greater Miami, Florida, USA.

René Buesa is retired; formerly Histotechnologist and Pathology Laboratory Manager at Mount Sinai Medical Center of Greater Miami, Florida, USA.

Michael Wilson is Professor and Vice-Chair at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, and Director of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Services at Denver Health, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Michael Wilson is Professor and Vice-Chair at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, and Director of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Services at Denver Health, Denver, Colorado, USA.

Joshua Kibera is an anatomical pathologist, Founder and CEO of The Pathology Network, Nairobi, Kenya.

Joshua Kibera is an anatomical pathologist, Founder and CEO of The Pathology Network, Nairobi, Kenya.

Ann Nelson is Senior Advisor and Director of LIS Programs at Pathologists Overseas, Infectious Disease Pathology Consultant at the Joint Pathology Center and Visiting Professor of Pathology at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Ann Nelson is Senior Advisor and Director of LIS Programs at Pathologists Overseas, Infectious Disease Pathology Consultant at the Joint Pathology Center and Visiting Professor of Pathology at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Andrey Bychkov is Director of Digital Pathology at Kameda Medical Center, Kamogawa, Japan.

Andrey Bychkov is Director of Digital Pathology at Kameda Medical Center, Kamogawa, Japan.

Mike Osborn is President of the Royal College of Pathologists and Consultant Histopathologist for North West London Pathology at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK.

Mike Osborn is President of the Royal College of Pathologists and Consultant Histopathologist for North West London Pathology at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK.

Tell us about your contributions to understanding the pathology workforce…

Stanley Robboy: During the time I headed the College of American Pathologists (2009–2013), our board recognized that American medicine was in a crisis and about to undergo a massive change. No one knew what form that would take – but, wanting to be proactive, we embarked on reviewing all aspects of pathology, including the workforce. I headed that thrust.

The two obvious elements of workforce are supply and the functions we serve. We now know that the numbers we established in 2013 (1) were too low, because the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) ignored pathologists who subspecialized. What we did correctly identify was the beginning of the retirement cliff, although the name was poor. It was not a cliff, but a gradual slide in which the number of people entering the profession was consistently lower than the number retiring. The highest rate of entry was from the 1960s to the 1980s; after that, the number of retirees overshadowed the number of new pathologists – and has, since 2000, been stable at about 600 each year.

A subsequent paper in 2015 (2) explored several important new facets. One was the taxonomy of pathologist activities – the settings of their work and functions. It became evident that this taxonomy was much more complex than anyone had previously conceived – but has proven crucial to developing workforce projections. A second was our ability to quantitatively project the demand by subspecialties. This understanding involved more than simply the numbers of specimens examined annually; it had to explore the technology needed to examine the specimens, which improved year on year. We also published how to measure those changes (3).

We are currently working with the AAMC to better understand the outdated methodology it used to provide workforce numbers for pathology and, I suspect, for all medical specialties. Our first joint publication is expected to emerge shortly.

Bruno Märkl: Wondering why it was so difficult to hire board-certified pathologists in Germany, I started to collect data such as total numbers of working pathologists, numbers of physicians in training, gender proportions, and so on. I discussed my insights with colleagues who encouraged me to publish – so I validated my data and compared the German results with numbers in other European countries and in North America (4).

Michael Wilson: Most of my work was on a pathology workforce survey via the group African Strategies for Advancing Pathology (ASAP) (5), the Lancet series on pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries, (6), and most recently the Lancet Commission on diagnostics (7).

Joshua Kibera: I am an anatomical pathologist and have practiced for eight years in Kenya. I spent four years as Head of Department at the Kenya Methodist University, then established my own anatomical pathology lab in 2017, which later merged with a cancer center servicing the Kenyan town of Meru and its environs. I have traveled to and been involved with pathologists in South Africa, Uganda, Botswana, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Somalia, Zambia and Kenya, so I am familiar with workforce challenges in sub-Saharan Africa.

Rene Buesa: From my arrival to the USA (from Cuba) in 1983 until my retirement in 2002, I worked first as histotechnologist, then as pathology laboratory manager. In that time, I made a number of contributions to the field in terms of safety and efficiency. After my retirement, I decided to share my managerial experience – which included running numerous surveys to determine workloads, staffing benchmarks, turnaround times, and productivity figures for every histology and cytology position and task in the USA and multiple other countries.

Ann Nelson: I have worked in pathology development in Africa since 1986 – I set up the first AIDS pathology lab in Kinshasa, Zaire. I have collaborated with Association of Pathologists of East, Central and Southern Africa (APECSA), the International Academy of Pathology, and other organizations to increase pathology capacity and utilization in Africa. With colleagues, we did a comprehensive survey of anatomic pathology workforce and capacity (8). I have also collaborated with and mentored many pathology leaders in sub-Saharan Africa.

Mike Osborn: The College has repeatedly raised the issue of workforce shortages across pathology services with the UK government and devolved nations’ administrations. We achieve this by attending parliamentary meetings, submitting responses and evidence to parliamentary groups, briefing parliamentarians to raise awareness of pathology, asking them to raise issues in parliament and with government on behalf of the profession, and responding to government consultations. In addition, we are closely involved with a range of other organizations directly and indirectly involved in workforce planning and resourcing. The groups consist primarily of high-level National Health Service (NHS) committees and other relevant stakeholder groups, but the College will work with any suitable stakeholder to highlight workforce issues and try to resolve them.

Issues raised have included calling for sufficiently trained staff, including increased numbers of biomedical scientists supporting medically qualified pathologists in integrated teams to achieve maximum productivity; improving retention of consultants and lab staff (having the right number of diagnostic staff in the right places, working in a supportive culture, is key to the delivery of an agile and resilient pathology service with patients at its heart); and building resilience in workforce by ensuring that staffing levels are sufficient to meet service expectations. This is not possible where staffing is aimed at covering minimum or average workloads.

Do you think the map accurately reflects pathology’s status in your region?

Andrey Bychkov: Data was collected from national registries with the assistance of local pathologists, international and local journal publications, and communication with local societies. The information was verified through personal communication with pathologists from the respective countries whenever possible. After validation, the data were classified as reliable, acceptable, or questionable, with questionable data excluded from the final analysis. All subspecialties were included, but residents and trainees were excluded.

SR: It is difficult for me to say whether it is high, correct, or low; at best, I can say it works. However, even though we are now seeing the rise of automation and artificial intelligence, there is little question that the incoming supply of US pathologists in the years to come will remain less than those retiring. For many years, pathology graduates could not find jobs. Suddenly, over this past year, I now continuously see the number of open positions far exceeding anything experienced for decades. Currently, there is an insufficient workforce – but we don’t control residency slots, so it is difficult to make predictions.

BM: Yes, the map appears accurate for my region.

MW: Yes, but the challenge is that workforce data are largely lacking for many regions – particularly in areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, where there are no formal registries or databases in most countries.

JK: For sub-Saharan Africa, the data appear more or less correct.

AN: The data include anatomic and clinical pathology, disciplines that are not combined in much of Africa – but the relative numbers seem correct.

MO: The heat map appears to show that there are enough pathologists in the UK – but this was not the case even before COVID-19 and the associated backlog and the situation has worsened since the pandemic. In addition, there are significant variations between regions and specialties. Northern Ireland, for example, currently has no pediatric consultant pathologists, and many rural locations across UK face greater workforce pressure with pathologist recruitment and retention than more urban centers.

AB: The UK data include not only histopathologists – also known as surgical or anatomic pathologists (AP) – but also other subspecialties, such as clinical pathologists (CP), microbiologists, chemical pathologists, and so on. The AP:CP ratio in the UK is 1.5:1, which is five to 10 times lower than in countries that don’t use the British system of pathology education and nomenclature. Furthermore, in many European countries, CP-equivalent jobs are occupied by other specialties, such as medical laboratory scientists, who are not pathologists and sometimes not even medical doctors. The UK has a histopathologist density of 23 per million people (a shortage; this would be yellow on the map). Projecting to the global level, my estimation would be that out of 108,000 practicing pathologists, only about 90,000 to 100,000 are surgical pathologists.

It’s important to add that our data don’t include residents or trainees, who perform a significant amount of work in pathology labs, but who are not board-certified. The number of residents varies widely by country, from less than 10 percent to up to 50 percent of all pathologists. For example, the USA offers a fixed number of just over 600 pathology residency slots each year, whereas India has recently raised that number to 2,350. I predict that, in just a few years, India will top the list.

What does the pathology workload and pipeline look like in your region?

SR: The workload for individual pathologists has increased over the years and I’m concerned about the dangers inherent in the rise.

In the early 1970s, a committee I headed for the Massachusetts Society of Pathologists specifically addressed workload numbers. The number we felt comfortable for an average pathologist at a secondary or tertiary center to handle annually was about 2,500 (one or two highly involved operations per day; three or four larger specimens; the rest biopsies). I now hear that pathologists commonly are expected to examine over 4,000 – sometimes considerably more – cases a year. That means the time per case becomes unbearably short, which I fear will lead to burnout and errors. A study we recently published reports that burnout rates for people with more than three years in practice have jumped significantly (9). This occurred whether or not the person was anxious or experienced burnout in residency. Burnout is now becoming the norm and I attribute this to unhealthy workloads.

BM: In Germany, we maintain the number of working pathologists. However, the rate of part-time workers is growing while full time equivalents are decreasing. I have no validated data concerning workload, but I estimate that the average number of cases per pathologist per year is around 10,000.

MW: The situation in most of Africa is woefully inadequate; the number of pathologists per population is a small fraction of what is needed to deliver necessary services at a population level. The average workload of a pathologist is highly variable, but in general low (except in some urban areas) due to inadequate healthcare systems, funding, and infrastructure – and a lack of awareness of the importance of diagnostics.

JK: Africa is a large continent whose different countries have operated in silos for historical reasons. Sadly, these silos extend into medical practice, where there is generally very little professional interaction between practitioners across the continent. Regional professional bodies have grown in strength over the last two decades because of geopolitical and economic unions such as the Southern African Development Community, the Economic Community of West African States, and the East African Community. APECSA has been instrumental in strengthening bonds between pathologists across the eastern and southern parts of Africa. Multinational pathology laboratory chains have played a role in elevating the status of pathology and further cementing relationships between pathologists in these regions. I am most familiar with eastern and, to some extent, southern Africa, so my opinions and observations are limited to these regions.

That said, there is a severe shortage of pathologists in East Africa (Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya and Somalia) and across southern Africa. There is currently relatively free movement of medical professionals across East Africa – a region that contains 200 million people served by just 300 pathologists. Training in East Africa tends to focus on creating general pathologists who can serve as administrators and practitioners in remote government hospitals. It’s expected that over half of these pathologists’ work will be in forensic pathology, so training is heavily oriented toward forensic pathology, hematology, and microbiology – the laboratory disciplines expected to make up the bulk of practice.

Most pathologists in eastern and southern Africa hold two or three jobs and are very busy. They often shy away from surgical pathology because of its sensitivity and because their training generally gives them limited exposure to histopathology. In Kenya and Uganda, most surgical pathology work is done by pathologists in the private sector or shipped abroad. Many surgeons consider it a luxury, so – in my estimation – 80 percent of samples are either not collected or are thrown away, even in Kenya (where surgical pathology uptake is highest).

RB: The USA averages are adequate, but pathologists are retiring and new MDs prefer better-paid specialties, so it is very likely that, by 2040, there will be shortages. In Cuba in 2020, there were 400 pathologists working in 110 departments across the country, along with 500 cytotechnicians and cytopathologists. The only workload information available was a total of 366,285 autopsies from 1991 to 2002, for an average of 30,524 per year and 3,330 per site.

Official US government statistics say that, in 2019, there were 21,292 active pathologists and 171,400 histotechnologists working in 9,111 histopathology and 3,995 cytology laboratories. The number of pathologists increased 13 percent from 2011 to 2019; histotechnologists are expected to increase 12 percent from 2016 to 2026. In 2011, there were 621,811 tests completed in those labs for an average workload of 68,248 tests per lab. Pathologists in the USA have a median of 3,000 cases per year; in Latin America, excluding Cuba, the mean is 2,100 cases per year.

AN: The pathology workforce has increased significantly in the past decade and there are more trainees, but there is still a deficit.

MO: Though there is variability across the 17 pathology specialties that the College covers, pathologists in general face great pressures through rising workloads and the increasing complexity of their work. Vacancies are also currently 10–12 percent and rising. The significant pressure on laboratory staff affects turnaround times for results, particularly in less automated specialties such as histopathology, a discipline in which requests to laboratories have increased by around 4.5 percent year on year since 2007.

Though some specialties are relatively stable when it comes to workforce, others are facing acute shortages – for example, pediatric pathology, with 24 consultant vacancies across the UK – creating considerable pressures on the service.

What future challenges do you anticipate in staffing and recruitment?

SR: Each staff member means a significant expense, and with reimbursements consistently dropping, all CEOs of hospitals and hospital chains will endeavor to prune payroll. If a national laboratory can do the same work at 75 percent of the in-house cost, why wouldn’t CEOs outsource the lab? Fortunately, many realize their own pathologists are critical intermediaries when clinicians need help understanding a patient’s disease, whether further treatment is needed, or even what expensive laboratory test should (and should not) be ordered. In-house pathologists often save hospitals bundles of money with their advice.

BM: I predict a systemic shortage of qualified staff over the next 10 to 15 years. By my calculations, we would need at least double the number of residents in training to cope with the growing workload.

MW: The pipeline for pathologists is small in many countries and, as a result, we are not even replacing the existing workforce as pathologists move, retire, or leave the profession. There are a few examples of small-scale successes, but the number of people entering the profession globally is far lower than necessary to expand the workforce.

JK: There will be a shortage of lecturers to train medical students in universities. We are not producing enough pathologists to fill this gap. There is already a chronic shortage of clinical and anatomical pathologists and the pace of training does not match population growth, increasing cancer testing, or the volume of surgeons, gynecologists, and endoscopists being trained.

RB: Unfortunately, my surveys don’t indicate the numbers of pathologists or supporting personnel needed per site or position. Without that knowledge, it is impossible to foresee future staffing and recruitment challenges, let alone the steps needed to address them locally or globally. We also cannot see whether or not present pathologist numbers are adequate or, if not, how many are needed – a question complicated by the fact that many international pathologists migrate to the USA in search of better salary or working conditions.

AN: Recruitment and retention are issues due to funding, priority, and the stability of governments and supply chains.

MO: A UK-wide survey of histopathologists conducted in 2017 found that only 3 percent of histopathology departments reported enough staff to meet clinical demand. Laboratory staff are under pressure to provide slides, which should happen within 24 hours, but regularly takes longer – in some places, up to 10 days. This directly and detrimentally impacts patient care.

Taking a broader view, 95 percent of patients will have a pathologist involved at some point in their healthcare journey. Evidence points to pathology services constituting 2–4 percent of the healthcare bill, meaning that the value of pathology services far outweighs their cost.

Our workforce is an aging one; around one-third of UK pathologists are 55 or over. When our most senior consultants retire in the next five to 10 years, there will not be enough trainees to replace them in numbers, let alone in knowledge and expertise.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought into sharp relief the vital need for pathology services. We must ensure that we learn lessons to ensure that the global pathology community has the resources it needs to help manage and mitigate the next global health emergency.

What is the most important action we can take today to ensure pathology’s future?

SR: The pathologist workforce in the hospital – and in local, state, and national pathology societies – must remain strong and provide the leadership and arguments to maintain good staffing.

BM: First, raise awareness of the issue. Second, increase of the number of residents in training. Third, heighten training efficacy – and consider reducing timelines (for instance, in Germany, five years instead of six). Finally, implement digital assistance systems.

MW: Advocacy. Until policymakers and governments make access to diagnostics a priority and provide the necessary funding, workforce challenges will not change. The lack of visibility of diagnostics is the single most important barrier to increasing the workforce; until it is addressed, little progress is possible.

JK: We need to rethink both pathologists’ training and the rules governing pathology practice. We should explore the possibility of training pathologists using digital slides, which would greatly increase the volume of pathology residents. We probably need to expand the scope of training of pathologists’ assistants and cytologists. The use of AI and assistive technology would be helpful increasing the efficiency of individual pathologists. Without increasing adoption of technology, Africa will never close the diagnostic gap.

RB: Every university pathology laboratory should accept pathology students on the condition of being trained in histology procedures. Also, increase the number of histology schools, both brick-and-mortar and online, to ensure the necessary auxiliary personnel.

AN: Continued emphasis on providing accurate, accessible, and on-time reporting of results. If pathology is an essential component of patient care and there are funds to pay staff, purchase consumables, and maintain infrastructure, it will be successful. Long-term, sustainable local (national) funding is needed.

MO: More training places for pathology specialties under pressure, better IT systems and connectivity, and digital pathology transformation programs.

We need to ensure that there are sufficient training places to meet future demand, so the College works closely with the government and organizations responsible for creating training places to ensure that pathology specialties are represented and included in plans to improve the overall number of trainees. We also need to attract medical undergraduates to take up pathology as a career despite stiff competition from other specialties. We have invested in an active program of engagement to encourage medical undergraduates to consider careers in pathology.

Digital pathology has the potential to improve patient care and support the pathology workforce by making the diagnosis and monitoring of disease much more efficient. In addition, it facilitates high-quality teaching. We need more investment in better IT for day-to-day work and to implement digital pathology more widely so that staff can work more efficiently and flexibly.

Digital pathology, and developments in technology-enhanced learning provide unique opportunities to support future training models (attracting high-caliber trainees), multidisciplinary learning, and new educational resource for trainees, practicing pathologists, scientists, and those in pathology-linked roles.

Pathology services underpin health systems around the world, but pathology is often overlooked. The global pathology community has a critical role in raising awareness among political leaders and policymakers to make the case for pathology for the benefit of patients.

Disclaimer: all data provided in this article are estimates. If you would like to add to or amend the data provided in this article, please contact Andrey Bychkov at bychkov.andrey@kameda.jp

References

- SJ Robboy et al., “Pathologist workforce in the United States: I. Development of a predictive model to examine factors influencing supply,” Arch Pathol Lab Med, 137, 1723 (2013). PMID: 23738764.

- SJ Robboy et al., “The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services,” Arch Pathol Lab Med, 139, 1413 (2015). PMID: 26516939.

- S Gupta et al., “An innovative interactive modeling tool to analyze scenario-based physician workforce supply and demand,” Acad Pathol, 2, 2374289515606730 (2015). PMID: 28725751.

- B Märkl et al., “Number of pathologists in Germany: comparison with European countries, USA, and Canada,” Virchows Arch, 478, 335 (2021). PMID: 32719890.

- African Strategies for Advancing Pathology Group Members, “Quality pathology and laboratory diagnostic services are key to improving global health outcomes: improving global health outcomes is not possible without accurate disease diagnosis,” Am J Clin Pathol, 143, 325 (2015). PMID: 25696789.

- ML Wilson et al., “Access to pathology and laboratory medicine services: a crucial gap,” Lancet, 391, 1927 (2018). PMID: 29550029.

- KA Fleming et al., “The Lancet Commission on diagnostics: transforming access to diagnostics,” Lancet, 398, 1997 (2021). PMID: 34626542.

- AM Nelson et al., “Oncologic care and pathology resources in Africa: survey and recommendations,” J Clin Oncol, 34, 20 (2016). PMID: 26578619.

- MB Cohen et al., “Features of burnout amongst pathologists: a reassessment,” Acad Pathol, 9, 100052 (2022). PMID: 36247711.