What initially drew you to pathology?

At college I was a basketball player, with an interest in sports physiology. When I started medical school, I assumed I was going to be a cardiologist.

However, at Vanderbilt University, we had a tremendous pathology course with a number of great lecturers, and I became fascinated with understanding the molecular mechanisms behind diseases.

As I rotated through various different disciplines during my third year of study, I found nothing from a clinical standpoint that particularly inspired me. But I really liked looking down a microscope and understanding the foundations of disease.

I particularly connected with some of my mentors who were focused on oncology diagnostics. That’s what got me interested in pathology, in general, and then in cancer, specifically.

What was your greatest achievement as a breast pathologist and researcher?

I was privileged to work with David Page, who is widely considered to be the father of modern breast pathology. He conducted some large epidemiological studies to establish the link between specific criteria and follow up in order to understand what a set of histologic findings really means in the wider context.

His studies led him to define atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia, and the implications around those diagnoses. Being involved in those discoveries was a great experience.

What motivated you to give all that up and take a career switch to head a cancer center?

To a large extent, David Page was also the inspiration for that decision. He was the first cancer center director at Vanderbilt, and a great role model of a pathologist taking on a cross-discipline leadership role.

Another mentor and role model was pathologist Hal Moses, who was responsible for achieving a National Cancer Institutes (NCI) designation for the Vanderbilt Cancer Center. That was a big inspiration for me.

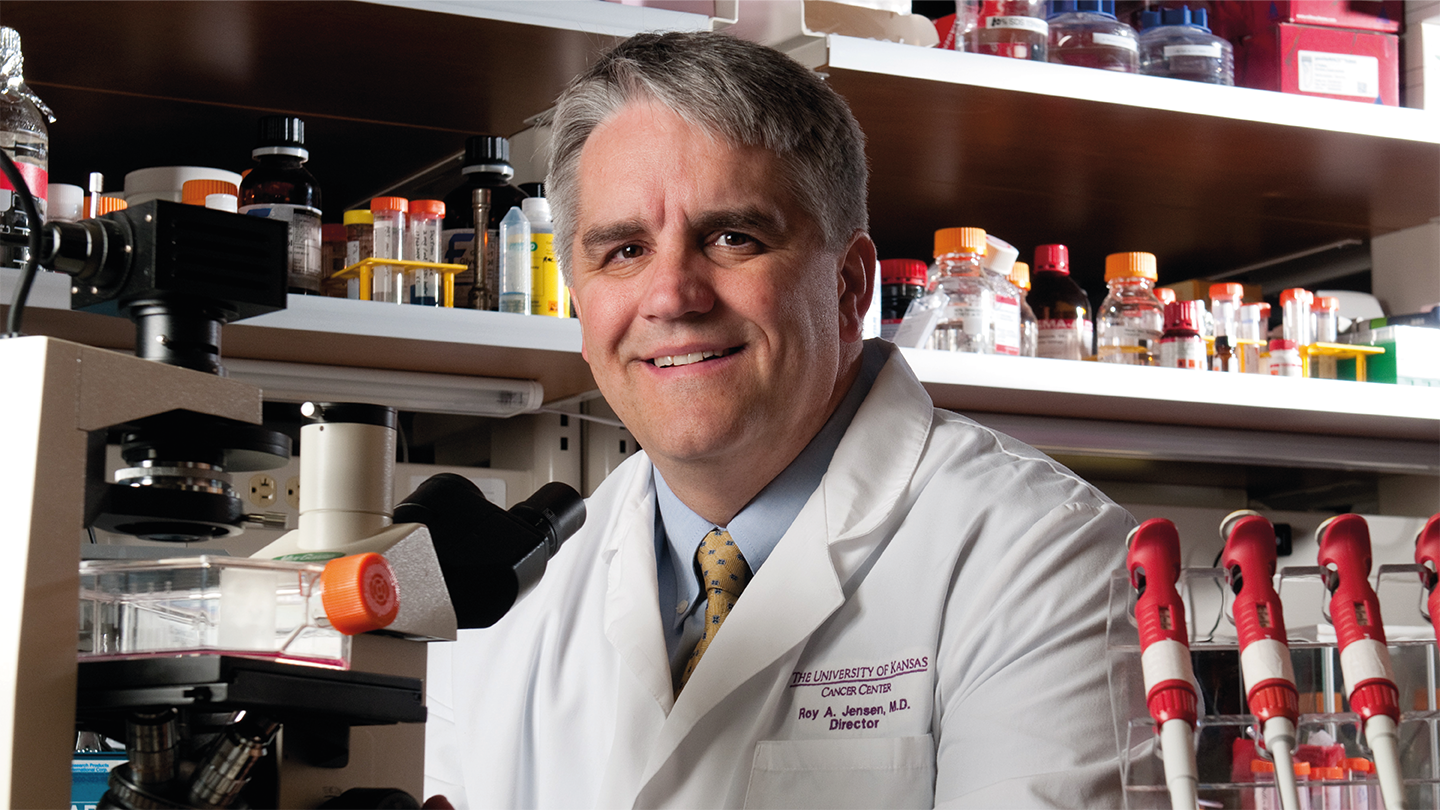

What have been your major achievements in your current role?

When I joined The University of Kansas Cancer Center, in 2004, the main priority was obtaining NCI designation. The first challenge was around building the culture – we needed the whole institution to agree to prioritize cancer.

That wasn’t easy, because stating that sort of priority tends to alienate folks in other specialties. But, over time, most people came to see that becoming an NCI designated cancer center was an important aspect of building a much stronger academic medical center in general, and we saw a lot more buy-in.

It took eight years to achieve NCI designation but, now that we have it, it has had a huge impact on the people of Kansas City and beyond. Back in 2004, Kansas City was the largest metropolitan area in the US that did not have an NCI designated cancer center. Fifteen percent of people diagnosed with cancer travelled to other cities for their treatment. Now, that number has halved, and we have completely changed the dynamic for accessing the best possible cancer care.

What are the biggest challenges for the cancer center now?

The growth in the cancer program at the University of Kansas has been significant since I arrived. Back then, we saw 1700 new cancer patients a year – now it’s closer to 8000. And our annual research funding has grown from around $14 million to over $80 million.

As a result of that expansion, we’re pretty much out of space in our current facility. So, for the past couple of years we’ve been planning a new cancer facility – of around half a million square feet – that will be equally divided over research and clinical activities.

That means that a major part of my role is fundraising. Over the last 20 years or so, we have raised somewhere between $1.3 and $1.4 billion.

My other major challenges are recruitment and setting out robust research programs.

What have you learned about communicating with non-medical lay audiences?

I think that is a critically important and very much underappreciated skill that academic medical center leaders really need to have.

One of my pet peeves is scientists delivering a talk to a lay audience using the same set of slides they used at a major scientific conference. The public has to be able to understand what it is you’re trying to achieve if you want to bring them along with you.

My approach is to pretend I’m trying to explain what I want to accomplish to my mom or grandma. If I can craft the presentation so that the audience understands what I’m doing, then I’ve hit the right note for the public to understand what I’m after.

What have you learned about leadership?

I knew that being a cancer center director was a fulltime job – I just didn’t realise how many fulltime jobs it was! I’ve had to learn to balance the tasks of fundraising, building the culture, advancing the clinical program, and educating the public. Communication has been key in achieving all that.

Alongside that, it has been critical to keep up to date with the science and be able to predict where the field is heading. Thirty years ago, there was little appreciation of the huge role the immune system would play in developing new cancer therapies. Now it’s front and center of almost everything we do. Being able to anticipate those trends and recruit the right mix of talent to be able to fully embrace them has been a key part of my leadership efforts.

In embracing those needs, some research has to take a back seat. That can be hard for some academics to take when their research has defined their entire career. But my job has to be to focus on the greater needs of the cancer center, and to try to bring my team along with that.

How do you see pathology’s role in cancer diagnostics developing?

We are now beginning to incorporate molecular diagnostics into cancer in a significant way. That makes it an exciting time for pathology. I believe that pathologists are the only specialists in medicine capable of integrating all the different diagnostic and molecular techniques, and they really should be running the diagnostic show.

The problem is that many senior leaders of pathology departments trained in the era before molecular techniques and can be hesitant in redesigning programs to implement the technology. But molecular diagnostics is set to become our bread and butter in oncology, so it’s essential that our residents have the skills in place to lead the way.

We need to ensure that training programs are feeding our residents the necessary skills in coordinating the various modalities and techniques in cancer diagnostics. That will be essential in ensuring the visibility and value of pathology as a discipline moving forward.

If you were given $1m to spend at the cancer center, what would you spend it on?

Honestly, I wouldn’t spend it until I added a few more zeroes. Even establishing a professorship at our institution might cost $2 million, which gives an indication of the price tag on achieving our goals.

Our new building is going to cost well over half a billion dollars, so $1 million seems like a drop in the bucket. My advice would be to keep that money in the pot and then keep fundraising and adding to it in order to really make a difference.