Educational games are everywhere. Though most of the software bearing that label is aimed at children in the early years of school, there’s also great, though mostly unexplored, potential in creating learning games as serious teaching tools for students in higher education. Though many would raise a cynical eyebrow, I can attest to the fact that educational gaming works.

Recognizing the potential value of game-based teaching some years ago, I developed a game generator for my students in the medical sciences. BrainSpan games are asynchronous multiplayer learning games, meaning that all of my students can play them if and when it’s convenient for them. They can test their knowledge, challenge one another, interact with their instructors, and gain more information, all from the comfort of their own computers – or even their mobile phones while on the go. This kind of on-demand studying lets students take advantage of downtime for review, and the “fun” aspect actually encourages them to study! As new generations of students become more and more immersed in the digital world, I think interactive online teaching tools like these may be the way of the future – and I encourage other medical teachers to get involved, too.

How BrainSpan was born

I have been using games in my courses since about 2003 – so for most of my teaching career – but it was 10 years ago that I came across an interesting asynchronous multiplayer game developed in Tasmania and got in touch with the fellow who was running it, a computer programmer called Mike Capstick (http://cybertrain.info/). He and I decided to work together to make a new game for the courses I was teaching at the time – a medical microbiology and immunology course for nursing students, and an infection, inflammation and immunity course for medical students. When we first created that prototype game, I wasn’t able to add or change my own questions, which was quite a pain, as my Tasmanian colleague had to do everything for me. It was another year before the dean of medicine hosted a Halloween party for the medicine dentistry students – and that’s when he first heard them rave about this “really cool game” they were playing in my class. They were all competing for points and really enjoying it. At the same time, they recognized that, while they were having fun, they were also learning new material and testing their knowledge of the old.

So one morning soon after Halloween, the dean called me into his office to tell me that we had to start running a game like that in all of the undergraduate medical courses – that is, 11 different classes spaced over two years. And at that point, I realized we needed to make and host our own version of the game, so that we could add and remove questions, update information and do all of the necessary maintenance ourselves. That moment was the birth of BrainSpan. Fortunately, the University of Alberta, Canada, has a special grant, known as the Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund, aimed at new educational projects within the university. Applying to that earned us C$128,000, but we got even luckier – the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry kindly topped it up with another C$100,000, and we got some additional funding from my department as well.

But getting the money together was only the first hurdle we had to cross. Next, I had to work with the central IT department to create our own purpose-built game from scratch. Initially, it didn’t turn out exactly the way I’d hoped it would, but given the costs of building something as complex and involved as an asynchronous multiplayer game, we simply had to do the best we could. The content, of course, was even more important than the structure. We needed to assemble a different set of custom game questions for each of the courses, so I hired three medical students for a summer. Their job was to write a list of questions for every course and then liaise with the course coordinators to make sure the questions were appropriate. I should say, they made questions for every course except my own two – because I wanted to write those lists myself!

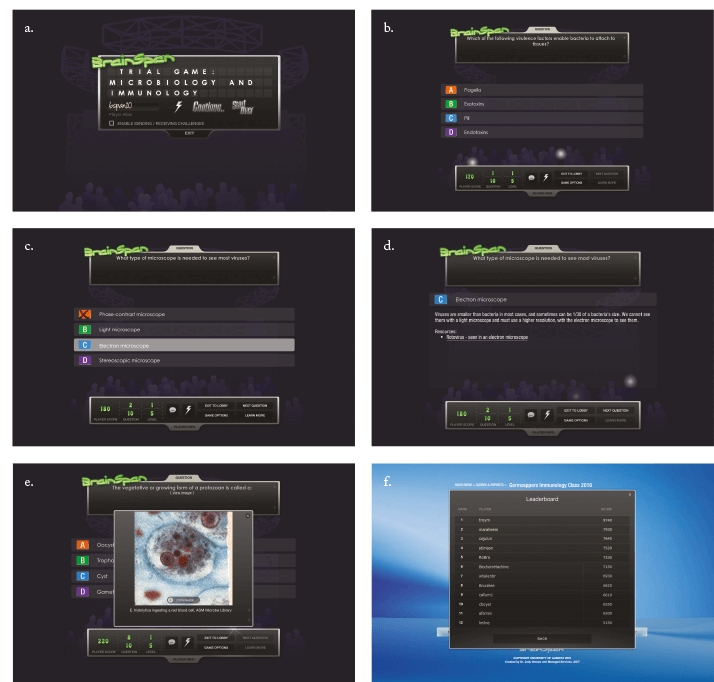

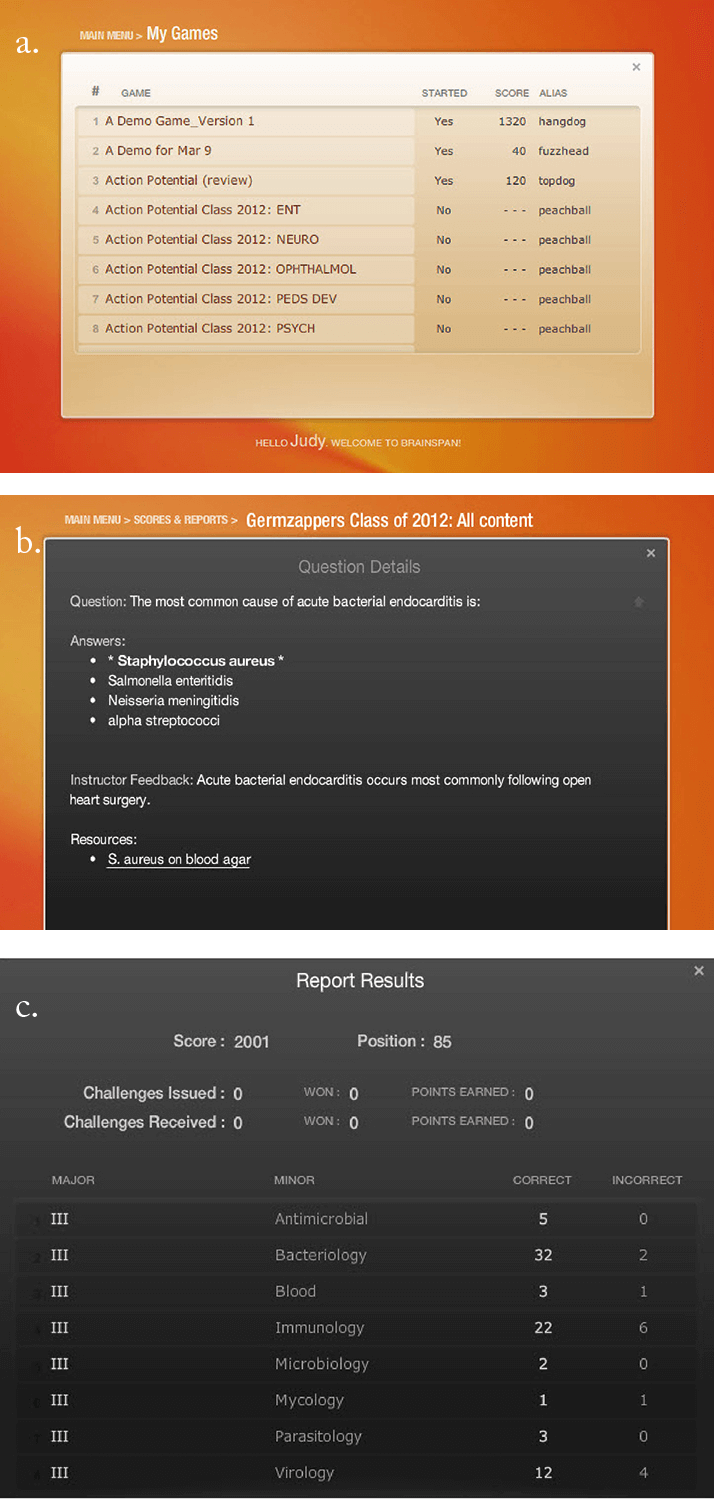

Testing the newly created games took the best part of a year, but the games were finally ready to launch in the fall of 2008. “Games” is perhaps not strictly accurate; BrainSpan is not a single game, but a game generator. You can use it to develop as many individual games as you need, and each game can be aimed at a specific set of players – you can add a class list, a subsection, a list of testers; anything you need. You can even include media in the questions and answers – images, weblinks, or even documents – to enrich their value.

But long story short, I’ve now been using the BrainSpan games for over seven years – and they’ve spread. Not only do I use them to teach nursing, medical and dental students microbiology; other professors use them for subjects from biochemistry to physiology to medical laboratory science. BrainSpan hasn’t spread beyond medicine and science yet, but I see its potential in almost any discipline. Right now, I would guess that there are about 2,000 students using BrainSpan each semester, but I hope that number continues to grow for a long time!

The evolution of educational gaming

When we first began using it, access to BrainSpan was restricted to students at the University of Alberta. Two years ago, the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry decided it would be a good idea to make the games available to people outside the university. We hoped that a small fee for the use of the games would help us obtain the resources we needed to keep the game running on our servers – and eventually, we wanted to grant other schools institutional access, now that we knew we had a valuable teaching tool. Unfortunately, the economic situation was not on our side. While outside users are still able to make BrainSpan accounts without needing a university-based email address, our plan of trying to host the games for other schools has yet to come to fruition.

But that doesn’t mean we’ve stopped expanding BrainSpan’s capabilities. Without extensive funding, we had to make creative use of resources – by which I mean that I partnered with a computer science professor who had four senior students in need of a project for one of their classes. Thanks to their hard work, we’re now able to offer both a mobile-friendly game and a BrainSpan app. Portable computing is becoming more and more important, especially as apps for remote diagnostics become increasingly effective – so why not get students engaged early with apps for their classes, too?

The key features of a teaching tool

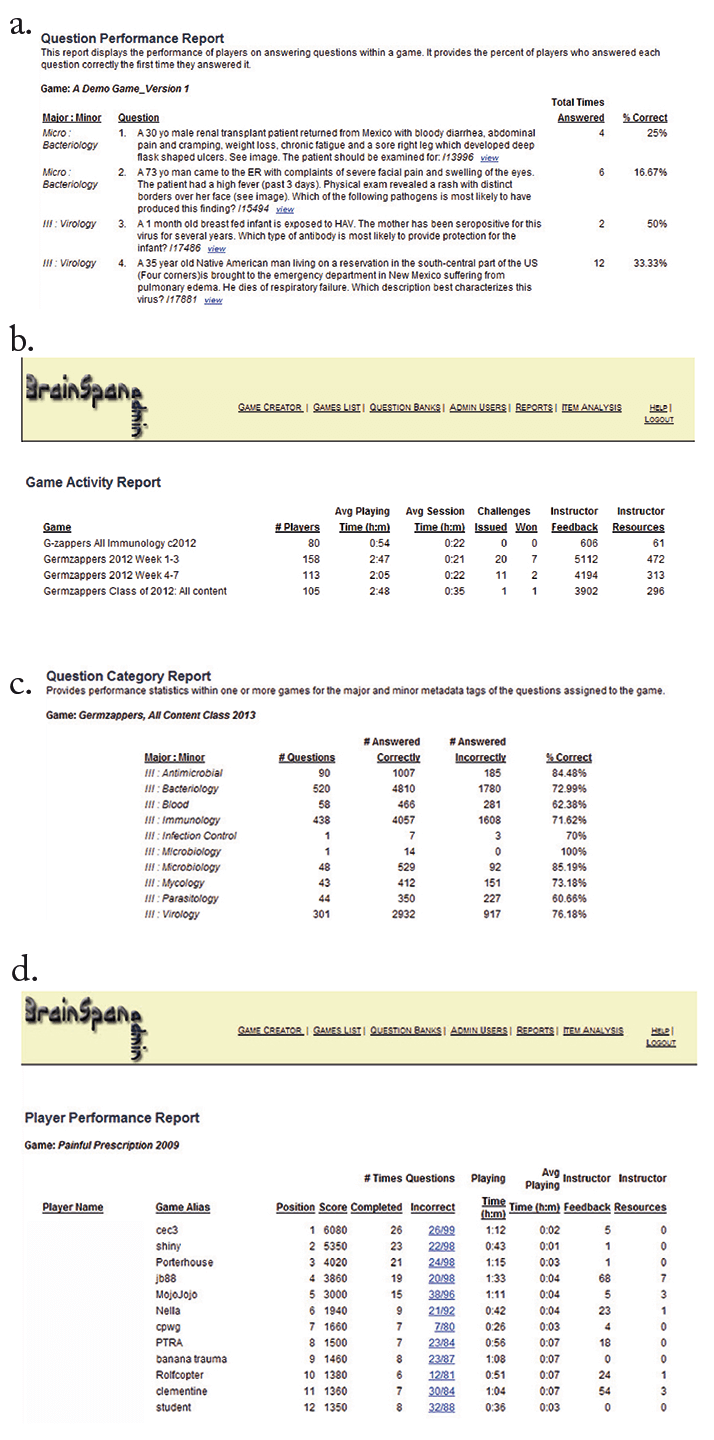

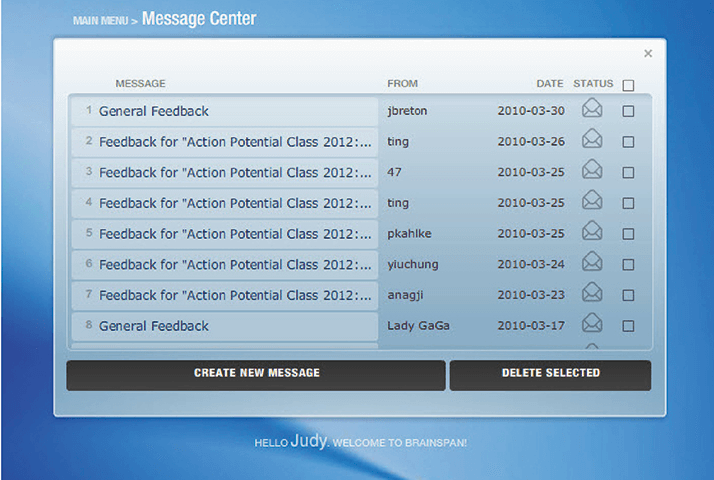

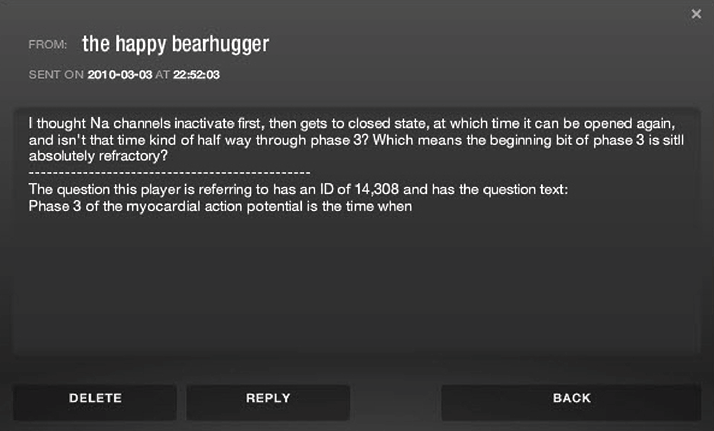

In my opinion, the most important feature of BrainSpan is the feedback it provides. Students using the games have access to more than one kind of feedback. The first and most obvious kind is the explanations given along with the answers to every question; they help students understand why their answers were right or wrong, rather than just marking it “correct” or “incorrect.” The other type of feedback, which I think is equally important, is retrospective. Users can check their own performance in a game, or over a number of games – at any point, they can call up a list of the questions they’ve answered incorrectly in the past, along with the correct answers. And it isn’t just the software itself that provides feedback. One unique aspect of our games that I really enjoy is that they facilitate student-teacher interaction. Students can send messages directly to their instructors from any question in the game – meaning that they can clear up confusion in the moment, rather than trying to remember it for later, and instructors can see exactly which subjects cause the most difficulties and why.

The direct messaging system is one way for teachers to see how good the questions themselves are, but it isn’t the only one, especially if the goal is to improve the games for future players. Instructors can also “vet” new questions to see how they work by putting them into a specific type of game that can’t be replayed. Students are then given access to the game and asked to complete it within a certain timeframe. We send the resulting game data file to our university’s department in charge of test scoring and questionnaires; they run item analysis statistics on the questions to help us understand how challenging the questions are, identify “trouble” questions, weed out distractors (the wrong answers in a multiple-choice question) and more. Being able to evaluate the quality of our questions and their suitability for our target populations lets us refine the games, making them even more useful for teaching.

The best teaching tools are the ones that can be used at students’ convenience – because those are the ones students are most likely to use! With BrainSpan, we’ve recently implemented an app, as well as a mobile web format of the game for users who aren’t able to download the app. Portability makes it more likely that students will engage with the games on the train, between classes, in waiting rooms, and anytime they might otherwise have difficulty studying with bulky textbooks and extensive notes. It also helps that students can start a game, do a few questions whenever they have time, and have their answers saved when they log off, so that they can pick up where they left off the next time they have an opportunity. BrainSpan’s convenience is one of the things that encourages students to get involved with it, so we’re pleased with how well it can be adapted to its users’ lives.

Success with struggling students

In the empirical sense, no one has ever been able to show consistently that any e-learning tools actually impact student success. Essentially, the bright kids will do well regardless of the resources available to them – and the less motivated students don’t use those resources enough to gain anything from them. I think that tools like BrainSpan actually offer the most benefit to students who struggle a bit. We all know that the plural of anecdote is not data, but my experiences have been pretty consistent – for instance, in a required class for an after-degree nursing course, I worked with a mother of four small children. Because of her lack of time and all of the other pressures of her life, she was only pulling off a grade of about 60 percent in the course. She got into BrainSpan and started doing that whenever she could find a few minutes – and in the end, she increased her overall score in the course by 20 percent! Ultimately, she ended up with a pretty decent mark, and that’s the sort of thing I’ve seen again and again from students who, after having difficulty, start using these less typical resources.

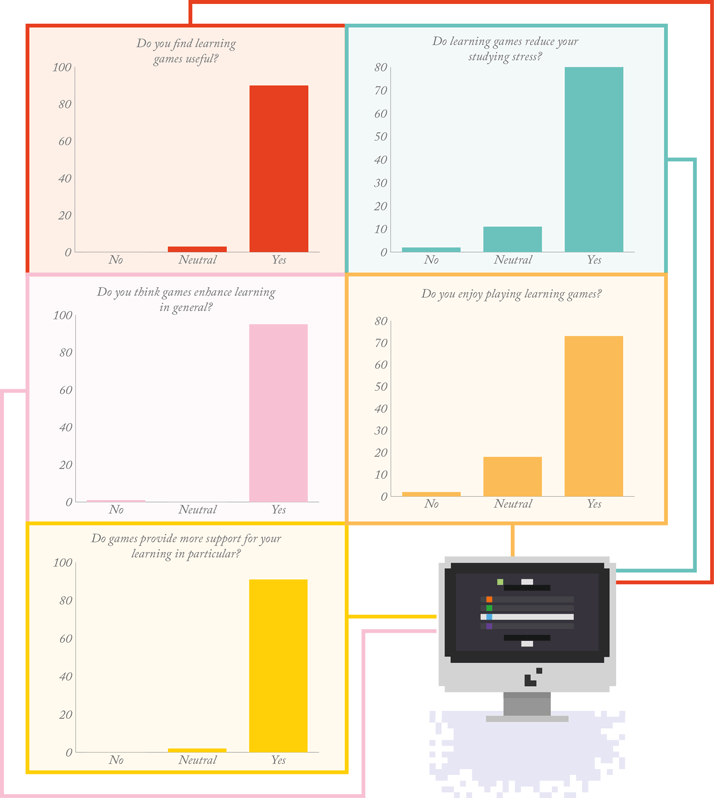

A number of years ago, I surveyed my students to find out what they thought of BrainSpan. In general, they were very positive. They valued that the instructors actually cared about their learning and provided them with extra resources. One student said, “I find it much more interesting to learn [through digital games] than by just going through the notes on my own. It inspires me to learn more when I get points for it and need to know the answers to move on. As well, it helps me know what to focus my studying on.” Another commented, “Some of the quizzes from other courses are very dry and not that relevant to what’s expected of you. But the MMI website is awesome for its relevance and motivational aspects. I love the drawings, the cases were very amusing and informative, and the Microbe Slayer game is a real hoot.” Students also found that the games were good for reviewing course materials. “For some subjects, like anatomy and microbiology, there is a lot of memorization, so the games are a fun way to reinforce the learning.”

Of course, the feedback is not all flawless. There are always a few students who don’t like computers and, by extension, e-learning. Students have made comments like, “I have never played digital games and therefore am reluctant to learn how to use them,” or, “I don’t really enjoy sitting in front of a computer; I would much rather be in a library going over lecture material.” But no one teaching tool will suit every type of learner, and I hope that, as newer generations of students are increasingly familiar with the digital world, BrainSpan’s popularity will continue to grow. In fact, much of the feedback I received dealt with the opposite problem – students wanted even more from the game, or wished they had more time to play it. These are the kinds of problems I like to hear, because they mean students are engaged and want to use BrainSpan!

Looking forward to future versions

I have a lot of ideas for the future of BrainSpan. One that stands out in particular is the ability to provide real, in-game motivation on an individual basis as well as between students. When we first built the BrainSpan game generator, we had to sacrifice one of my favorite aspects of the Tasmanian game that inspired it. In that game, the points you earned by answering questions correctly weren’t just for bragging rights – you received rewards when you reached a certain number of points. You could use those rewards to buy things like strength or immunity – things that added another dimension to the gameplay. I wish a similar reward system were present in the current version of BrainSpan. At the moment, you play, you accumulate points, and you can use those points to challenge other students – you wager points on a particular question, and if the person you challenge gets it right, you lose those points. If they answer the question incorrectly, you win extra points. But that’s actually another thing I’d like to change about the current version – the challenge system isn’t set up very well, as you need to exit the game in progress to visit the message center where the challenges are sent. Unfortunately, that means the challenges – which I think are a great way for students to motivate one another and enjoy a spirit of camaraderie – aren’t used as much as I’d like at the moment.

Another thing I’d like is to be able to link questions together. Right now, they’re all self-contained, but one day it would be good to be able to run case studies. We could have a set of attached questions that harken back to the case, allowing students to work through it in a manner similar to the continuing medical education healthcare professionals must complete after qualifying. This was part of the plan for BrainSpan from the start, but unfortunately we lacked the funds to bring it to fruition. I still hope we’ll have the opportunity to implement case studies one day, as I feel that they would be very beneficial for students on track to becoming medical professionals.

I think the game would probably have to be rebuilt to incorporate the changes I’d like to see, especially the ability to receive a challenge in real-time while you are playing a game. I’d like a pop-up notification that said something like “You have been challenged – will you accept this challenge?” The ability to earn rewards, whether in the form of merit badges, ranks, titles like “grand master,” or anything else, might involve a bit of work as well – but certainly not as much as adding the ability to use your points to purchase attributes that help you compete with other students. I have a lot of ideas for those attributes: things like getting twice the points wagered in a challenge if you have earned a particular merit badge, or immunity to challenges so that you don’t lose points even if you miss a question.

Some changes to the internal workings of the game generator would be good, too; for instance, I’d like game creators to have more administrative power. At the moment, we can’t do simple things like print out lists of questions from our games, or have the messages students write within the game sent directly to the instructor’s email address. We could also use some more complicated functions, like the ability to copy a whole game over and start fresh when you want to add a new student cohort without losing the questions you wrote for the earlier game. Right now, you have to create the new game from scratch and import all of the questions you want to use, which is much more time-consuming. It’s not just for instructors, either; students would benefit from a few tweaks to the interface, too. For example, we can include images with questions or answer explanations. Right now, users can click on the images to enlarge them, but can’t move them on the screen or enlarge them on touchscreens by pinch-zooming. Little things like that would add a lot of convenience for everyone.

The only thing I may never be able to change about BrainSpan is its availability. In my soul, I believe that these types of learning resources should always be free to access. Of course, I understand that there is always a cost associated with building and hosting software, and I understand that the faculty sponsoring BrainSpan’s existence does need funds to keep it online. Still, it would be nice if one day, we found a way to make learning games available to everyone, without having to charge a fee to do it.

Tips for teachers

It would be wonderful if more educators – not just in medicine and the sciences, but in all disciplines – took advantage of new media resources like BrainSpan. If you decide that asynchronous multiplayer games are the right tools for your classroom, remember that they need reinforcement, just like any other teaching tool. If you want your students to use the resources you provide, you have to remind them and advertise the resources in class. For quiz games in particular, it’s important to make sure they stay current by keeping up with the course curriculum, making sure the questions are relevant and the answers correct, and including feedback that helps students learn not just what the right answer is, but why.