The inspiration:

Patients with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome have malformed skeletons and fragile bones. Nearly five years ago, two publications in Nature Genetics demonstrated that these patients have specific mutations in the NOTCH2 gene (1)(2). At the time, Ernesto Canalis’ laboratory at the University of Connecticut had been working on Notch signaling for about 10 years. They believed that the only way to study the rare bone resorption disease was to recreate those mutations in a mouse model.

The inspiration:

Patients with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome have malformed skeletons and fragile bones. Nearly five years ago, two publications in Nature Genetics demonstrated that these patients have specific mutations in the NOTCH2 gene (1)(2). At the time, Ernesto Canalis’ laboratory at the University of Connecticut had been working on Notch signaling for about 10 years. They believed that the only way to study the rare bone resorption disease was to recreate those mutations in a mouse model.

The experiments:

In the 2011 papers, individuals with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome underwent exome-wide sequencing. Mutations were found in exon 34 of NOTCH2 upstream of the domain required for protein degradation, creating a stable, truncated NOTCH2 protein (1)(2).

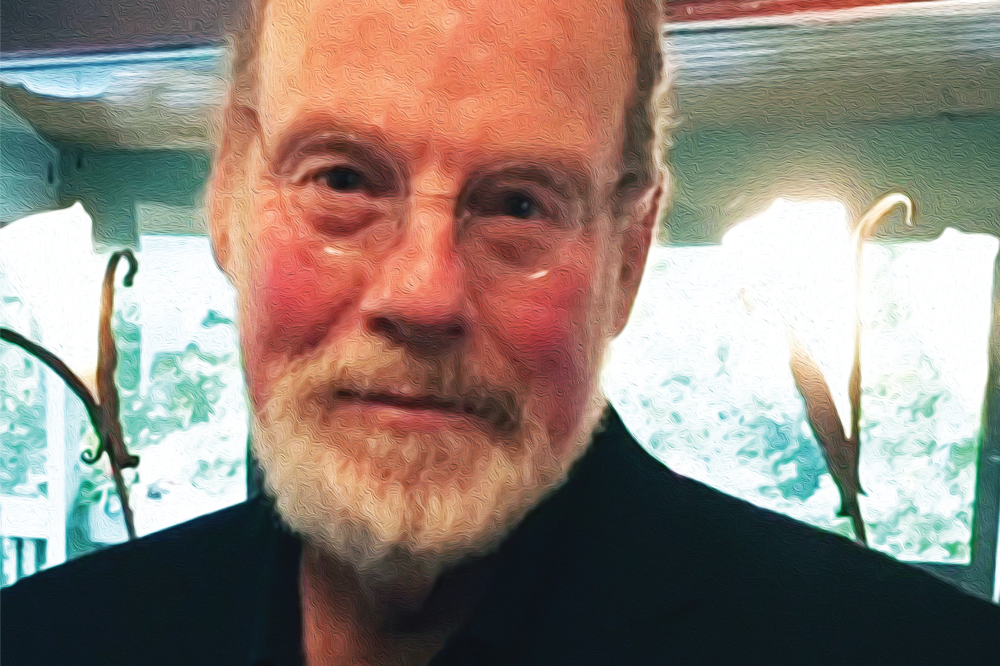

“We have discovered that the Hajdu mutant mouse has increased bone resorption because of an increase in bone-resorbing cells,” says Canalis (see Figure 1). “It is conceivable that the use of specific anti-resorptive agents might ameliorate the bone disease.” But the mouse model lacks the craniofacial and neurological abnormalities of human disease, so the researchers are currently aging the animals to see whether these manifestations appear (3).

The implications:

“We have learned a great deal about mechanisms of bone turnover and bone loss, and confirmed that NOTCH2 plays a critical role in these processes. The model will allow us to pursue other disorders associated with mutations in the Notch signaling pathway.” What are Canalis and his laboratory doing now? “We are studying the function of B cells in Hajdu mutant mice, as NOTCH2 is known to play a key role in these cells. We are also creating additional mutants affecting other members of the Notch signaling pathway in an effort to relate them to other genetic disorders associated with Notch signaling.”

The experiments:

In the 2011 papers, individuals with Hajdu-Cheney syndrome underwent exome-wide sequencing. Mutations were found in exon 34 of NOTCH2 upstream of the domain required for protein degradation, creating a stable, truncated NOTCH2 protein (1)(2). “We have discovered that the Hajdu mutant mouse has increased bone resorption because of an increase in bone-resorbing cells,” says Canalis (see Figure 1). “It is conceivable that the use of specific anti-resorptive agents might ameliorate the bone disease.” But the mouse model lacks the craniofacial and neurological abnormalities of human disease, so the researchers are currently aging the animals to see whether these manifestations appear (3).The implications:

“We have learned a great deal about mechanisms of bone turnover and bone loss, and confirmed that NOTCH2 plays a critical role in these processes. The model will allow us to pursue other disorders associated with mutations in the Notch signaling pathway.” What are Canalis and his laboratory doing now? “We are studying the function of B cells in Hajdu mutant mice, as NOTCH2 is known to play a key role in these cells. We are also creating additional mutants affecting other members of the Notch signaling pathway in an effort to relate them to other genetic disorders associated with Notch signaling.”References

- MA Simpson et al., “Mutations in NOTCH2 cause Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, a disorder of severe and progressive bone loss”, Nat Genet, 43, 303–305 (2011). PMID: 21378985. B Isidor et al., “Truncating mutations in the last exon of NOTCH2 cause a rare skeletal disorder with osteoporosis”, Nat Genet, 43, 306–308 (2011). PMID: 21378989. E Canalis et al., “Hajdu Cheney mouse mutants exhibit osteopenia, increased osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption”, J Biol Chem, 291, 1538–1551 (2016). PMID: 26627824.