The Integration Equation

Proposed pathologist guidelines for radiology consultations

At a Glance

- Diagnostic workups can be complex and require the input of multiple medical specialists

- To optimize diagnostic processes and use of samples, pathologists and radiologists should work together

- When there are issues with a patient’s biopsy, a pathologist’s first port of call should be the radiologist

- Our role as members of the health care team is evolving – and by working closely with our colleagues, we stay relevant and can be most helpful for our patients

When a patient is diagnosed with a lesion requiring further investigation, the diagnostic workup is frequently complex. It typically involves interaction between the initial clinician (usually a primary care physician), a specialist, one or more radiologists, and often several laboratory physicians, not to mention numerous support staff, nurses, physician assistants and laboratory technicians. In the setting of a teaching hospital, the environment can become even more complex as trainees in all of the involved departments are brought in as well.

With a straightforward case – for example, a 4.5 cm spiculated lung mass discovered on screening chest CT scan, subsequently biopsied, and found to be adenocarcinoma – the issues may seem trivial; however, correlating the various ancillary imaging and laboratory studies may prove challenging, potentially leading to diagnostic delays or misinterpretations. The need to assemble all forms of imaging and laboratory information can be tedious and exhausting when the results are reported in different systems or under several different tabs in the electronic medical record (EMR).

Start a conversation

Discordance between radiology and pathology studies compounds these problems. As good practice, frequent verbal communications between pathologists and radiologists ensure that we recognize and minimize potential diagnostic confusion prior to issuing the pathology report. The radiologist-pathologist conversation may provide valuable feedback to the radiologist (because the pathologic findings may add to their understanding of imaging findings and improve interpretive skills), and to the pathologist (who may develop a better appreciation of the clinical question asked with the biopsy and provide a more relevant pathologic answer).

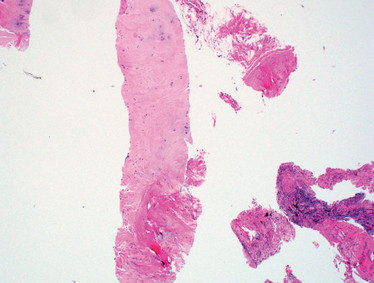

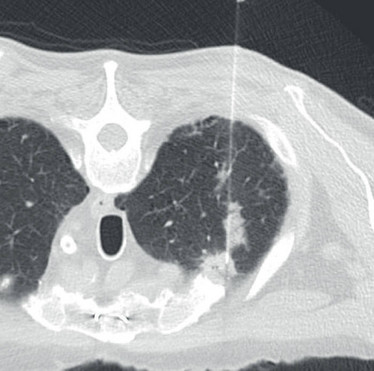

A recent example on our service involved a right upper lobe (RUL) lung nodule that contained primarily fibroconnective tissue with pauci-cellular chronic inflammation, occasional mildly atypical pneumocytes, and prominent fragments of cartilage (see Figure 1A). Given the findings, we considered pulmonary hamartoma in the differential diagnosis. In our practice, we try to discuss all benign or negative biopsies with the radiologist. Specific to this case, the radiologist’s (paraphrased) response was, “Well, I guess anything can happen, but it really looks like cancer and it doesn’t have the expected features of a hamartoma. However, because of the location of the biopsy needle within the peripheral lung nodule, it’s possible that cartilage could have been incidentally sampled from the chest wall (see Figure 1B).”

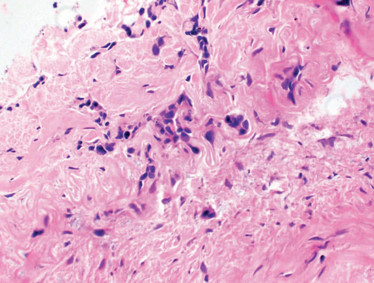

With this additional verbal information, we cut deeper sections into the biopsy tissue block and discovered a small focus of cells suspicious for non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC; see figure 1c). Importantly, the radiologist was able to convey the degree of suspicion for malignancy much more thoroughly to the pathologist in direct conversation than in the biopsy requisition, which has only limited ability for nuanced communication.

Figure 1. A. Biopsy of RUL lung nodule with prominent fragment of cartilage (possible hamartoma); H&E stain, original magnification 40x. B. Image from CT-guided biopsy demonstrates biopsy introducer cannula within the same spiculated RUL lung nodule (features not suggestive of hamartoma); note the close proximity of both the nodule and the biopsy cannula to the right first costochondral cartilage. C. Rare atypical cells found on deeper section (suspicious for NSCLC); H&E stain, original magnification 400x.

When should a pathologist contact the radiologist? We propose the following situations:

- negative/benign biopsy result,

- surprising/unexpected finding on the biopsy,

- clarification of specific requests for the biopsy, and

- insufficient material on the biopsy.

Negative or benign biopsy

We define a negative biopsy as one that “is negative for any pathologic process or contains only nonspecific findings.” In this setting, sampling during the biopsy may have missed the intended lesion, or the findings may reflect a process that is not the radiographic lesion of concern (for instance, inflammation adjacent to a malignancy). Additionally, the biopsy may have been performed on an atypical or unusual radiographic presentation of a typically benign process with a lower level of suspicion for malignancy, such as an apical cap or rounded atelectasis.

A discussion with the radiologist may help guide the diagnostic comment; it can also help inform the ordering clinician that the lesion was likely missed by sampling error or is a benign process (meaning that it can be followed without the urgent need for a repeat biopsy). Without an assured radiologic-pathologic correlation comment, the patient may be subjected to an additional, unnecessary needle biopsy or even a more invasive surgical biopsy.

Surprising or unexpected finding on the biopsy

There are at least two obvious advantages to reviewing unexpected findings with the radiologist. First, it serves as an excellent learning opportunity for the radiologist to get immediate follow-up on the biopsy they just performed; second, it can provide a clue that the findings might not necessarily be reflective of the lesion of concern. Furthermore, the discussion with the radiologist may provide very important context for the pathology findings.

One recent example from our service was the discovery of papillary-type lung adenocarcinoma on a biopsy in a patient with a history of melanoma. The purpose of the biopsy was twofold: to confirm stage and to obtain material for molecular testing for the melanoma. The radiologist was surprised at the finding, but pointed out that the patient had numerous and bilateral rounded nodules that were still very suspicious for metastatic melanoma. With this insight, the pathology report included a diagnostic comment to indicate the biopsy finding might not reflect the overall radiology findings, and further sampling of other lesions might be necessary to confirm the suspicion of metastatic melanoma and obtain diagnostic tissue for ancillary studies.

Clarification of specific requests for the biopsy

The number of specialized studies that need to be performed on a small biopsy as standard of care continues to grow and significantly impacts the manner in which pathologists handle these small specimens. A biopsy may be performed as part of an initial workup or, if the patient has an established diagnosis, its purpose may be to obtain tissue for a specific test or clinical trial. The reason for the procedure should be available from the requisition or EMR – but, if not, the pathologist should contact the ordering physician or interventional radiologist to clarify the clinical question.

In our practice, we usually contact the radiologist first. Why? The radiologist has just seen the patient and is usually well aware of the purpose of the biopsy. They also tend to be easier to track down; there may be multiple oncologists in the EMR, and the oncologist we contact first may not be familiar with the reason for the biopsy. This issue is likely to be situational for different practice environments, and we encourage each pathology group to develop its own best practices for whom to contact with tissue handling questions.

Insufficient material from the biopsy

This problem occurs in every practice in the world. We must convey the finding of an inadequate biopsy to the procedural radiologists so that they can consider the particular circumstances of the biopsy. If the discovery is not explicitly communicated to the radiologist, they may not get this important feedback at all. In our experience, radiologists are very receptive to these discussions and appreciate the feedback.

Multiple reasons can account for insufficient or suboptimal biopsy material: the procedure may have been terminated early due to complications such as bleeding; an inexperienced trainee without sufficient guidance may have been involved; the adequacy evaluation by the cytotechnician may have been unrealistically generous, thus prematurely ending the procedure; or the tissue collected was adequate, but suboptimal handling in the laboratory resulted in loss of tissue at the grossing station or in the tissue processor.

Without discussing the outcome of the biopsy, we lose the opportunity to understand and prevent similar problems in the future. Occasionally, the biopsy is suboptimal because the lesion is in an anatomically difficult location to sample with a needle biopsy. In this situation, the radiologist may recommend a surgical approach to further sampling if clinically indicated. (It is very unlikely for this suggestion to be made by the pathologist.) In this setting, input from the radiologist may save significant time and money.

For this collaborative paradigm to work, both radiologists and pathologists need to be receptive to an open and collegial environment that encourages reflection and discussion of their findings. This may challenge the initial diagnostic impression for either diagnostician; however, in our experience, the increase in collegiality from close and frequent interactions reinforces a shared sense of teamwork between radiologists and pathologists, creating a strong and respectful bond that allows for a little bit of ego bruising.

In all areas of medicine, the diagnostic process increasingly involves more players using newer technologies, and the pathologist’s role is changing. Technologies, such as point-of-care molecular testing or in vivo microscopy, have redefined – and will continue to redefine – the function of the pathologist in the diagnostic process of many diseases. Pathologists’ ability to recognize our evolving role as just one part of the diagnostic team will enable us to interact effectively with our clinical colleagues and provide us with the best opportunity to optimize our value in the future.

Suggested Reading

- J Sorace et al., “Integrating pathology and radiology disciplines: an emerging opportunity?”, BMC Med, 10, 100 (2012). PMID: 22950414.

- AS Oh et al., “Imaging-histologic discordance at percutaneous biopsy of the lung”, Acad Radiol, 22, 481–487 (2015). PMID: 25601302.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare. The National Academies Press: 2015.

Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and Chief of Pulmonary and Renal Pathology at the David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, USA.

Professor of Radiological Sciences, Director of Thoracic Interventional Services, and Vice Chair of Radiology Education at the David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, USA.