At a Glance

- Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) work toward optimal patient management by a group of specialized health care professionals

- The concept is popular and has existed for some time, but reliable data on the benefits of MDTs is harder to come by

- Pathologists should sit at the center of the MDT as leaders, not just as participants

- MDTs will probably be the way of the future and this is our opportunity to advance the profession and the practice of medicine as a whole

Most pathologists in hospitals or clinics are familiar with the multidisciplinary team (MDT) concept. A group composed of specialized health care professionals representing every aspect of patient care, concentrating on optimal patient management, has become the norm in many jurisdictions. But what advantages do they really convey, and what is our role on the team?

Understanding MDTs

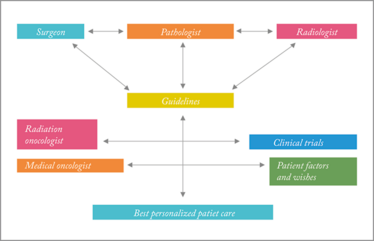

What exactly is an MDT? It can be defined as “collaborative patient care by a team of clinical and allied specialists whose collective diagnostic and therapeutic intent is individualized patient management (1).” For example, a breast cancer MDT is typically composed of pathologists, breast surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, imaging specialists, breast cancer nurse specialists, and an MDT coordinator or secretary (2).

Despite their popularity, the question of whether or not MDTs actually improve patient outcomes has yet to be fully answered. Studies have shown that they increase adherence to guidelines, foster better teaching environments, and improve overall clinician and team satisfaction (5)(6)(7). Nevertheless, their survival benefit remains difficult to prove. Why? Partly because of the lack of appropriate controls – it can be difficult to compare patients whose treatment has involved an MDT against those whose hasn’t. And even when the two groups can be compared, confounding variables abound.

One standout study was a retrospective, comparative, non-randomized interventional cohort study (8) that examined the effect of MDTs on nearly 14,000 patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in Scotland between 1990 and 2000. Prior to 1995, no MDTs were involved in the care of any of these patients; in the period from 1995 to 2000, Greater Glasgow (n=7,672) alone implemented a breast MDT, whereas services outside the intervention area (n=6050) did not. The trial featured no patient selection bias, had a contemporaneous control group, and used a strict definition of an MDT that included evidence-based guidelines, weekly meetings, and audits. The result? A noticeable difference. Before 1995, Greater Glasgow had a significantly worse five-year Breast Cancer Specific Survival (BCSS) at 71.3 percent, compared with 73.6 in the surrounding district (HR 1.11, 95% CI [1.00–1.20], p=0.04). After the introduction of MDTs to Greater Glasgow, that area’s breast cancer-specific mortality was 18 percent lower, and its all-cause mortality was 11 percent lower, with a five-year BCSS of 79.2 versus 75.9 percent (HR 0.82, 95% CI [0.74–0.91], p<0.001). In 2000, MDTs were introduced to the remainder of West Scotland.

A schematic diagram of an MDT, showing the pathologist’s role.

The pathologist’s role

The pathologist is – or should be – at the epicenter of a comprehensive management approach. Why? Because we integrate information from the radiologists and surgeons and provide the actionable data for patient care. However, it’s not enough just to attend meetings and read our reports; we must be true participants in the team. An MDT performance assessment tool developed in 2011 (9) contains a rubric for pathological information that goes from 1 (“no provision of pathological information”) to 5 (“review of pathological images”), with provision of pathological information from a report or account as the midpoint. The rubric also provides assessment guidelines for histopathologists, again ranging from 1 (“nil/impedes contribution of others”) to 3 (“contribution inarticulate or vague”) to 5 (“articulate and precise specialty-related contribution”). For Canadian pathologists who use the CanMEDS framework, the assessment covers the roles of collaborator, scholar, and health advocate.

Collaborator: provision of inclusive reports (including the translation of pathology reports and the enabling of integration and clinical-pathology-radiology correlation)

Scholar: promotion of evidence-based practice

Health advocate: stewardship and resource utilization (including the need for specific sample types or tests, such as biopsy or biomarker analysis)

How well are pathologists carrying out these roles? The 2011 study results, which came from the observation of five MDT meetings (three different MDTs addressing 112 total patients), were not favorable. When rated for information presentation, pathologists scored an average of 2.85 based on a surgeon’s observations and 3.20 based on those of a psychologist. The contribution scores were even worse at 2.03 and 2.15, respectively – below a performance contribution of “inarticulate or vague.”

When asked what we do, many of us may reply, “Diagnose disease.” But that must not be our only function; many experts predict that artificial intelligence may one day replace diagnostic histopathology. An even more sobering study found that pigeons could be easily trained to accurately identify images of breast cancer (10). Interestingly, there was an affinity between the pigeons and histopathology; they weren’t able to interpret radiologic images with the same accuracy. Our current and future value lies in our professional role. Locally, we are links in a larger collaboration, providing feedback on preanalytic factors, working on quality assurance, and developing testing algorithms. On a larger scale, we participate in working groups to share information, create guidelines, and select biomarker tests, among other things. We also have a part to play outside the lab – and outside medicine as a whole – acting as educators, advocates, advisors, and leaders.

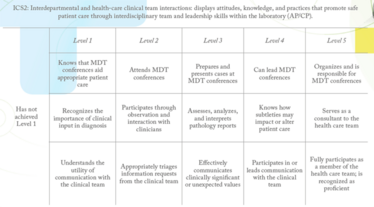

Table 1. A summary of the milestones involved in MDT participation and leadership. Adapted from (11).

The training ethos

This greater view of the role of pathologists was captured in the Pathology Milestone Project, which highlighted knowledge, skills, attitudes, and other attributes necessary for pathology residents to achieve Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies. The milestones are grouped into five levels: 1) starting residency, 2) advancing through residency, 3) continuing advancement with a majority of milestones consistently demonstrated, 4) residency graduation, and 5) “aspirational” goals for continuing development – a level only a small percentage of residents are expected to achieve.

The milestones cover actions related to basic laboratory tasks, diagnosis, reporting, teaching, laboratory management, patient safety, pathologist wellbeing, and much more. Not least among them are the interaction-based goals, which specifically include effective participation in – and leadership of – MDTs (see Table 1).

However, as a profession, we suffer from a number of deeply ingrained negative stereotypes (12). This is largely because the profession generally appeals to introverts. However, as noted in recent reviews and publications, introverts possess many characteristics that are increasingly recognized as key leadership qualities. These include good attention to detail, dependability, analytical thinking, integrity, and work ethic. To advance pathology and the practice of medicine as a whole, we have to start honing those skills for leadership and individual achievement. Our attention to detail becomes an ability to focus on the matter at hand and to be held accountable by others. Our dependability yields a commitment to service and an ability to form strong partnerships with our non-pathologist medical colleagues. Analytical thinking allows us to assess and evaluate the information we encounter during MDT meetings, and to strategically align our current efforts with the future of our institutions and our profession. Our integrity demonstrates our character and professionalism to other members of the team. And, finally, our work ethic makes us achievement-oriented and ensures that we not only set goals for ourselves and our MDTs, but also reach them. To be good team members, we must develop all of these skills – and we must remain self-aware and ensure that we always listen to our colleagues and make decisions as a single unit, rather than a dozen disparate doctors. A good introvert skill!

It’s worthwhile to keep in mind that William Henry Welch (1850–1934), often referred to as the Dean of American Medicine and the champion of evidence-based medicine, was a pathologist.

What’s next?

You’re convinced of the value of MDTs. You’re convinced of your own profession’s vital role in them. But what do you do next? If you’re interested in subspecialty practice, the answer is simple: join an MDT. If subspecialization is not for you, consider joining a special interest group to further the practice of pathology by contributing to workload distribution schemes, transparent workload accounting, or clinical research. If you’re a director or otherwise have authority over the way your laboratory or institution is run, then ensure that there is protected time for MDTs, and encourage leadership opportunities for those of us who show an aptitude.

Of course, all of this is easier said than done. How we approach and solve the dilemmas around subspecialty practice, research, and professionalism will determine our future. But this is the way forward for the profession, for medicine and – most importantly – for our patients and our society.

Judith Hugh is Laboratory Site Chief and Divisional Director of Anatomic Pathology at the University of Alberta Hospital and Professor and Lilian McCullough Endowed Chair in Breast Cancer Research at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

- NJ Look Hong et al., “Multidisciplinary cancer conferences: exploring obstacles and facilitators to their implementation”, J Oncol Pract, 6, 61–68 (2010). PMID: 20592777.

- C Taylor et al., “Benefits of multidisciplinary teamwork in the management of breast cancer”, Breast Cancer, 5, 79–85 (2013). PMID: 24648761.

- KS Saini et al., “Role of the multidisciplinary team in breast cancer management: results from a large international survey involving 39 countries”, Ann Oncol, 23, 853–859 (2012). PMID: 21821551.

- GW Prager et al., “Global cancer control: responding to the growing burden, rising costs and inequalities in access”, ESMO Open, 3, e000285 (2018). PMID: 29464109.

- J Prades et al., “Is it worth reorganising cancer services on the basis of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)? A systematic review of the objectives and organisation of MDTs and their impact on patient outcomes”, Health Policy, 119, 464–474 (2015). PMID: 25271171.

- B Pillay et al., “The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: a systematic review of the literature”, Cancer Treat Rev, 42, 56–72 (2016). PMID: 26643552.

- BW Lamb et al., “Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review”, Ann Surg Oncol, 18, 21116–2125 (2011). PMID: 21442345.

- EM Kesson et al., “Effects of multidisciplinary team working on breast cancer survival: retrospective, comparative, interventional cohort study of 13 722 women”, BMJ, 344, e2718 (2012). PMID: 22539013.

- BW Lamb et al., “Teamwork and team performance in multidisciplinary cancer teams: development and evaluation of an observational assessment tool”, BMJ Qual Saf, 20, 849–856 (2011). PMID: 21610266.

- RM Levenson et al., “Pigeons (Columba livia) as trainable observers of pathology and radiology breast cancer images”, PLoS One, 10, e0141357 (2015). PMID: 26581091.

- WS Black-Schaffer et al., “Training pathology residents to practice 21st century medicine: a proposal”, Acad Pathol, 3, 2374289516665393 (2016). PMID: 28725776.

- M Schubert, “The Last Respite of the Socially Inept?”, The Pathologist, 3, 19–25 (2014). Available at: bit.ly/1Fs4FSH.

Judith Hugh is Laboratory Site Chief and Divisional Director of Anatomic Pathology at the University of Alberta Hospital and Professor and Lilian McCullough Endowed Chair in Breast Cancer Research at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.